Proceedings of Borderlines Interdisciplinary Postgraduate

Conference 2003.

Proceedings of Borderlines Interdisciplinary Postgraduate

Conference 2003.© 2006 and beyond Juliet Hewish. ISBN: 978-0-9552229-8-6.

| View XML source |

| Home |

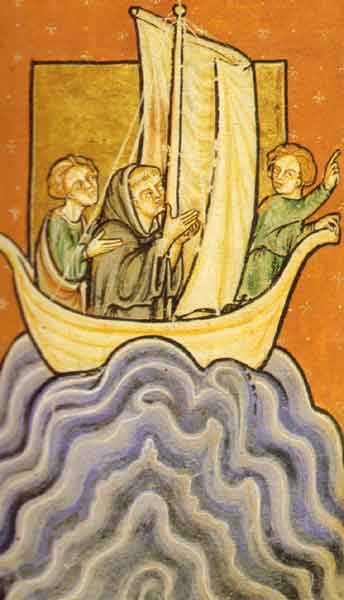

Proceedings of Borderlines Interdisciplinary Postgraduate

Conference 2003.

Proceedings of Borderlines Interdisciplinary Postgraduate

Conference 2003.

© 2006 and beyond Juliet Hewish. ISBN: 978-0-9552229-8-6.

1. In accordance with the theme of Borderlines 7, the aim of this paper shall be to re-examine the traditional borderlines established between clerical and lay audiences by the examination of a selection of manuscripts containing homiletic hagiography in Old English and Medieval Irish.2 Focussing upon the text and the context as a key to the writers and readers of these medieval compilations, the manner in which homiletic saints' Lives have been transmitted and how they might have been used by medieval audiences will be explored. Ultimately, the purpose of such a reader-response approach would be to provide an insight into contemporary concepts of genre and the borderlines established between ecclesiastical and secular writing, but unfortunately this is beyond the scope of this present paper. For the present, I shall be focussing upon four manuscripts in which anonymous homiletic and hagiographic material is found: the Blickling Homilies (Princeton University Library, W.H. Scheide Collection 71), the Vercelli Book (Vercelli, Biblioteca Capitolare, CXVII), the Leabhar Breac (Dublin, Royal Irish Academy 23 P 16) and Dublin, King's Inns Library, 10.3

2. The Blickling Homilies (Princeton University Library, W. H. Scheide Collection 71, is a collection consisting of eighteen complete texts or fragments,4 preserved in a tenth-century manuscript.5 The exact dating of the contents of this collection has been the cause of some controversy,6 although it is clear that this manuscript is a compilation of texts composed by different authors: Clemoes has argued that ‘single authorship can be ruled out from the start on stylistic grounds’. 7 Written by two scribes, the manuscript is incomplete, having lost four quires at the beginning and another after quire nine, so that it is impossible to tell the extent of the original collection. As it now stands, however, this manuscript is the second largest collection of anonymous vernacular homilies surviving from the Anglo-Saxon period. The eighteen homilies surviving are ordered according to the church year, a fact that would suggest that the Blickling collection may have been intended to be read as a preaching text, although this would not exclude it from being used in private, for devotional reading. That the intended audience of this homiliary was a mixed congregation of clergy and laity is suggested by a number of internal references. In Homily X, for example, we find the traditional (oral) exhortation of the homiletic opening, followed by a listing that can only mean that this text is aimed at a general congregation:

Men ða leofostan, hwæt nu anra manna gehwylcne ic myngie & lære, ge weras ge wif, ge geonge ge ealde, ge snottre ge unwise, ge þa welegan ge þa þearfan …8

‘Dearest men, behold, I now admonish and exhort everyone, both men and women, young and old, wise and unwise, rich and poor’

3. Likewise, in Homily IV the audience is urged to pay tithes and attend church:

Sanctus Paulus cwæþ þætte God hete ealle þa aswæman æt heofona rices dura, þa þe heora cyrican forlæteþ, & forhycggaþ þa Godes dreamas to geherenne. Forþon ne þearf þæs nanne man tweogan, þæt seo forlætene cyrice ne hycgge ymb þa þe on hire neawiste lifgeaþ.9

Later in the same homily, reference is made to the fulfilment of the duties of bishops and priests and the punishment reserved for those who fail their obligations, suggesting that it is not the laity alone at whom these homilies are aimed:‘St Paul has also said that God commanded all those who forsake their church and neglect to hear the songs of God to pine at the door of heavens kingdom. Therefore, no man need doubt this: that the forsaken church will not take care of those who live in her neighbourhood.’

Se mæsse-preost se þe bið to læt þæt he þæt deofol of men adrife, & þa sawule raþost mid ele & mid wætere æt þon wiþerweardan ahredde, þonne bið he geteald to þære fyrenan ea, & to þæm isenan hoce.10

‘The priest that is slow to drive out the devil from a man and to quickly rid the soul of the adversary with oil and water shall be assigned to the fiery river and the iron hook.’

4. Although the saints' Lives found in this collection are no longer attached to Gospel readings, that they were intended as models to expound upon the scripture is suggested by the fact that they share features traditionally associated with the homiletic. Thus many begin with the formulaic men þa leofstan11 or make reference to the Gospels with phrases such as se godspellere ... awrat or her segð þæt (e.g. ‘S. Andreas’, ed. Morris, p. 229).12 That purely homiletic material (I-XII in Morriss edition) should be combined with homiletic saints' Lives in such a collection should hardly surprise if we accept this mixed audience; the rationale to do so may have been driven by purely practical considerations, as Mary Clayton has suggested:

As the Mass was probably the only context in which the people received regular religious instruction and as all the necessary texts appear to have been contained in the homiliary, these collections for preaching to the laity contained a mixture of homilies and saints' lives.13

5. It is not beyond the bounds of possibility, therefore, that the Blickling Homilies may represent a collection not unlike that for which the hagiographical homilies were originally intended, and that they were written to be preached before a mixed audience. However, it should be borne in mind that much of the Anglo-Latin hagiography of the pre-Conquest period, which was presumably aimed at a purely clerical audience, was also found in compilations containing both hagiographical and non-hagiographical material (consider MS Oxford, Bodleian Library, Digby 39, for instance).

6. When we turn to the Vercelli Book, we find a collection containing not only religious prose but also poetry, presenting something of a generic enigma (Gatch has labelled it ‘among other survivors of the Anglo-Saxon age ... sui generis’).14 Vercelli is not a homiliary per se - for the manuscript is not arranged in liturgical order - but it contains homiletic pieces, frequently connected by a concern with penance and eschatology, particularly the Last Judgement.15 The prominence given to these concerns may suggest, as Éamonn Ó Carragain has convincingly argued, that the Vercelli Book represents an ascetic florilegium brought on a pilgrimage to Italy by an elderly individual to whom the preoccupation with age and death found in the collection appealed.16

7. Whatever the history of the final compilation, as in the Blickling Homilies some of the individual pieces found in the Vercelli Book appear to have been written for a lay audience, which is exhorted to give alms and pay tithes (compare Blickling Homily IV):

He sceal fæstan begangen 7 þa lufian mid clæne ælmessan 7 mid mycle forwyrðnesse habban on his life. 7 he sceall beon ælmesgeorn for Godes naman 7 for his sawle.17

Since the order of this collection is not liturgical, however, and the material sometimes difficult to imagine being incorporated into the Mass, it would seem that the Vercelli Book collection was intended for private reading; Kenneth Sisam has characterised the collection as ‘essentially a reading book’.18‘He must be diligent about fasts and love them together with pure almsgiving and have great integrity in his life. And he must be charitable for the name of God and for his soul.’

8. Similar ambiguity appears to surround the question of audience of the Middle Irish hagiographical homilies found in the Leabhar Breac and MS King's Inn 10. The Leabhar Breac Maic Aedhagain, the ‘Speckled Book of Mac Egan’19 was compiled in the early fifteenth century and consists of largely religious and devotional tracts. These include an epitome of the Old and New Testament; early Christian legends based upon the apocryphal Gospel of Nicodemus and Acts of the Apostles; the apocryphal acts of St Quiriacus, and other pieces related to the Invention and Exaltation of the Holy Cross; the Félire Oengusso (‘Martyrology of Oengus’); and the ancient Irish law concerning the observance of Sunday, litanies and so on.20 The saints' Lives in this manuscript include Patrick, Bridget, Colum Cille (Columba), Stephen, George, Michael and Martin. Amongst the non-religious pieces are a history of Philip of Macedonia and Alexander the Great and the satirical Aislinge Maic Conglinne (‘The Vision of Mac Conglinne’). Most of the manuscript contents are in Irish, although Latin (of a rather poor quality) is interspersed in some pieces.

9. Like the Vercelli Book, then, in the Leabhar Breac we seem to have an enigmatic collection of texts apparently unsuited, in its present form, to any liturgical function and intended presumably therefore for private reading. Certainly private reading would be suggested by the inclusion of non-devotional pieces. Unlike either the Vercelli or Blickling collections, however, we are fairly certain (on account of the linguistic forms there found) that the Leabhar Breac was compiled long after the texts included in it had been written, perhaps as much as three centuries after, allowing for a greater degree of misrepresentation on the compiler's part.21 As an analysis of the homilies included in this manuscript will reveal, a number of them must have been originally intended for liturgical use, whatever their later function may have been.

10. At a first glance, the religious material of the Leabhar Breac would appear to be aimed at a congregation in orders, perhaps members of the Céli Dé (‘brotherhood of God’). Thus we find included in the fifteenth-century manuscript the Félire Oengusso (‘Martyrology of Oengus’), a prose version of O' Moelruain's metrical rule for a Céle Dé (IX ‘Incipit riagail na celed n-de, o moelruain cecinit’) and a piece on the Céle Dé or clerical recluse (CCIII ‘Do celi de, no di clerech reclesa’). In addition to this are two companion pieces, one on the occupations of a priest and the other on the occupations of a monk (CC ‘Do monorugud sacairt’ and CCII ‘Do monorugud manaig’ respectively).

11. When we turn to the homilies of the Leabhar Breac, the evidence so far accumulated appears to be supported by internal reference. Thus we find in the homilies for Palm Sunday (XVII. ‘Domnach na Himrime’), on the temptation in the desert (XIX. ‘De Ieiunio Domini in Deserto’), on the Pentecost (XXI. ‘De Die Pentecosti’) and on charity (XXV), exhortations to ‘fratres carissimi’, translated into Irish as ‘A brathri inmaine’22 In the homily on the Archangel Michael (XXVII), moreover, we find a description of what should be done on the festivals of the saints, a list which likewise appears to be aimed at the clergy:

Tri herdaige dlegar do denum i sollamnaib na noem 7 na fhíren; is e in cetna erddach, celebrad 7 procept brethri Dé; is e imorro in t-erddach tanaise, edpairt chuirp Crist meic Dé bíí 7 a fhola, de chind in phopuil Cristaide; is e in tres erddach, biad 7 étach do thabairt do bochtaib 7 do aidelcnechaib in mor choimded na ndúla.23

‘Three ceremonies only are required to be performed on the festivals of the holy saints and righteous: the first is the celebration and preaching of the word of God; the second is the sacrifice of the body and blood of Christ, the son of the living God, on behalf of the Christian people; the third is the giving of food and clothing to the poor and needy of the great Lord of the elements.’

12. What Atkinsons edition does not reveal, however, is that these lines are interspersed with the Latin equivalent. There are three ways in which we might read this evidence. In the first instance, Latin may be used to impart authority; Latin was generally considered to be of greater status than the vernacular and its inclusion may have endowed the homily with greater eminence. Secondly, it might suggest that the audience/readership at whom this text was aimed may have needed the Irish in order to explain the Latin. However, since the text is predominantly in Irish and the Latin not very difficult, this explanation seems lacking. Why bother to use Latin at all if it will not be understood? It seems more likely that the intended audience/readership was every bit as bilingual as the texts author, who chose to use Latin to emphasise the message of the Irish at important points in the text.

13. When we examine the homily on almsgiving (XXVI ‘Do’n Almsain’), where we might most expect reference to a lay audience, again we find evidence that would suggest that the homilist adapted his material for a clerical audience. Once more Latin and Irish are freely interspersed, the Gospel reading with which the homily begins being given in both languages, phrase by phrase:

Cum ergo facies elimoisinam noli tuba canere ante te sicut hipocrite faciunt in sinagogis 7 in vicís ut honorificientur ab hominibus. In tan didiu dogéna almsain nachas-commáid amal dogniat inna brecaire i ndálaib 7 ind-airechtaib do chuinchid a n-anoraigthe o dáinib.24

‘Cum ergo facies elimoisinam noli tuba canere ante te sicut hipocrite faciunt in sinagogis 7 in vicis ut honorificientur ab hominibus. When, then, you are going to give alms, do not boast of it as do the hypocrites in meetings and in assemblies to seek honour for themselves from people.’

14. Further supporting the view that this text was aimed at a clerical audience, almsgiving is conjoined with fasting and prayer, and presented as having both a physical and spiritual manifestation, of which the spiritual elements are praised far more highly than the physical:

Et haec eleemoysna excellentior est quam corporis 7 is ferr iar fhír in almsa-sin andaas in almsu do'n churp; multo enim maius est animam ad imaginem Dei factam de spiritualibus alimentis satiare et de peccati nexibus soluere, quam corpus de limo terrae creatum de terrenis necessitatibus adiuuare. Uair is ferr co mor do almsain in animm da-rónad iar ndeilb 7 iar cosmailius Dé, do shásad o shástaib spirutaltaib in fhorcetail diadai, a thaithmech didiu ó chúibrigib cinad 7 peccad 7 targabal, andáas in corp da-rónad do chriaid in talman d'fhortacht 7 do shaerad do na hecentadaib talmandaib im-mbí.25

Again it would seem as if we have a text aimed at an audience familiar with constant interchange between Irish and Latin, which we might well assume, therefore, to be from a learned, clerical background. Furthermore, as well as the inclusion of the Gospel reading found in the homily on St Martin, for example, we find references in the homilies on Saints George, Stephen, and Peter and Paul to the fact that these saints are celebrated at ‘this time and period’ (‘i n-ecmoc na ree-si’). This would seem to suggest that these homilies were to be read on the saints’ festivals, probably as part of the liturgy.‘Et haec eleemosyna excellentior est quam corporis 7 these alms are better than physical alms; multo enim maius est animam ad imaginem Dei factam de spiritualibus alimentis satiare et de peccati nexibus souere, quam corpus de limo terrae créatum do terrenis nechessitatibus adiuuare. For the giving of alms which has been done by the satisfied spirit, made in the image and likeness of God, for spiritual satisfaction of the divine teaching and then for liberation from the bonds of guilt and sin and transgression is much better than that done by the body, which is made from the clay of the earth, to assist and to deliver itself from the earthly necessities in which it is.’

15. Yet, having shown the collection to be aimed primarily at clerics, there are instances in which a lay audience appears to be intended. The most obvious case must be the Sermon to Kings (XVI ‘Sermo ad Reges’), a piece that appears in no other extant homiliarium and which F. Mac Donncha has labelled ‘sui generis’. 26 The homily directly addresses the king and can hardly have been intended for a monastic audience. Furthermore, in Homily LXXXVIII on the Maccabees (‘Procept na Machaabdai’), we find an exhortation which seems unlikely to have been aimed at clerics (although priests are singled out in the phrase preceding) and most probably had a lay audience in mind:

Is coitchend tra do fheraib 7 do mnáib in forectul-sa, ar dlegar díb imalle co ro-p ferrda a fheidm fognuma do Dia: cathaiged tra co calma in t-í shailes i nDia.27

‘This exhortation is common to men and women, for it is required alike from both that their energy of service to God should be virile: let everyone who hopes in God fight bravely.’

16. Such passages certainly support Mac Donncha's assertion that these homilies ‘are intended for the populace and not for scholars’,28 yet seem to contradict the evidence described above. The most obvious conclusion would appear to be that the Leabhar Breac is made up of individual pieces taken out of their original context and adapted, to varying degrees, to the requirements of this later compilation. The resulting collection, like its anonymous Old English counterpart the Vercelli Homilies, appears to have been a non-liturgical work, possibly aimed at an unnamed aristocratic patron with a particular interest in the affairs of the church.29 As mentioned before, however, it must be borne in mind that the manuscript witness to these homilies is approximately three centuries older than most of the original texts contained within it. It is instructive, therefore, to consider another manuscript witness to some of these homilies, since it is clear that compilations such as the Leabhar Breac and Vercelli Book were not the only forms in which such material has been handed down to us.

17. Turning to examine MS King's Inn 10, therefore, we find a manuscript dedicated to religious matter. Written later in the fifteenth century than the Leabhar Breac, the manuscript contains no scribal colophon or date, but three hands are noted by the cataloguer: a) ff. 1-8v, 57c 16-58v, 60 r (verso illegible); b) ff. 9r-16v, 59; c) ff. 17r-57 c 15; with a fourth hand appearing briefly in ff. 7d m-8 a i.30 Homilies in common with the Leabhar Breac in terms of subject matter, though not necessarily form, include: Lives of Patrick, Bridget and Colum Cille, the Passion of Longinus, and the Passion of John the Baptist. Despite some cross-over in terms of content, however, when we consider the individual homilies in detail (and for the current paper I shall focus specifically on the Homily on the Life of St Martin of Tours, which begins on f. 48 d.1 and concludes on f. 51 a 22), the different approaches of the two manuscript compilers soon come to light.

18. For instance, when close analysis is done, it is found that a great deal of the Latin found in the Leabhar Breac version is cut from the King's Inns manuscript and replaced with Middle Irish paraphrasing. Thus if we compare part of section 5 of Stokes's edition of the Leabhar Breac Life (LB) with the corresponding section of the Life found in King's Inns (KI), for instance, we find:

LB: .i. Aut enim unum odio habebit et alterum diliget .i. ut fieri debet. Odiet diabulum et diliget deum 7 dobéra miscais 7 míchátaid do diabul amal dlegair. dobéra immurro grad cride 7 menman dodia.

‘Aut enim unum odio habebit et alterum diliget .i. ut fieri debet. Odiet diabulum et diliget deum 7 and he will bear hatred and abhorrence to the Devil, as is right, but he will give love of heart and mind to God.’

KI: Oir noco cumaic duine corro cara na hirchradhe imaille 7 na suthaine amal forgles Ioin apstal in ni sin ir raides cidh pe duine carus in doman ni fil grad inn athar nemdha ann. No ármiscnighfid diabol amal is comadhas 7 carfaid dia.

‘For a man is not able to love temporary and eternal things at the same time, as the apostle John testifies in relation to this matter when he says: Whichever man loves the world has no love of the heavenly father in him. Or he will hate the devil as is merited and he will love God.’

19. A similar example is found at the end of section 19, where the Leabhar Breac Latin ‘dixit judex’ is replaced with the Irish ‘ráid in brithem’ in King's Inns. Unlike the Leabhar Breac, the Irish expansions of this Latin are written as glosses, and are superscripted rather than integrated into the text (see the passages corresponding to Stokes' Ch. 1, 4, 12, 16 and 41).

20. What does this combined evidence suggest about the aims and intentions of this manuscript compiler and the audience for whom he was writing? In the first instance, the fact that the Latin in this manuscript is glossed would suggest that it was intended as a reading rather than a preaching book, calling into question Mac Donncha's claim that we ‘are dealing with a work not intended for readers, but for listeners’.31 Secondly, the fact that some of Latin is translated into Irish might suggest that the intended audience was not competent in Latin and were either of the laity or lower classes of clergy. As mentioned above, however, this seems a less likely explanation. Instead, it is suggested that the movement between Latin and Irish may be an indication of the status of Latin over Irish and the bilingualism of our translator, who switches unconsciously between the two languages. If this is the case, then it can be assumed that he was from a clerical background, a suggestion supported by the contents of this manuscript, and that he may have been writing for an audience of similar origin.

21. In conclusion, then, we find in both Old English and Middle Irish instances in which hagiographical homilies appear to have been placed in compilations intended both for preaching to a mixed audience (Blickling) and for devotional reading (Vercelli, Leabhar Breac and King's Inns). Of those apparently intended for reading purposes, the Leabhar Breac appears to be have been aimed at a patron interested in both ecclesiastical and secular literature, the Vercelli Book at an individual, lay or cleric, concerned with eschatology, whilst Kings Inns alone suggests a purely clerical reception. As those apparently aimed at individuals reveal, however, the compilations in which these texts now survive were almost certainly a far cry from the context in which these works would originally have been found. Although the author and his immediate contemporaries may have had very distinct ideas as to what it meant to be writing a homiletic hagiography, it would appear that as time passed, in both the English and Irish traditions, these generic boundaries had, to some extent, broken down.

1. I would like to express gratitude to the Irish Research Council for the Humanities and Social Sciences (IRCHSS), who provided the funding for this research as part of their doctoral research scholarship scheme.

2. For the purposes of this article, the hagiographic homily is distinguished from other branches of hagiography by its relation to the Gospel: it begins with a scriptural quotation upon which the following homily is based, in which the virtues and doctrines extolled in the scripture are shown to have been epitomised by the saint. In some instances, however, the preceding scriptural quotation has been removed by later manuscript compilers, making generic classification somewhat ambiguous.

3. The manuscripts chosen for this paper have been dictated by my own work upon the Life of St Martin, which appears in all four, and by my intention to focus solely upon anonymous pieces for the present. It might seem strange that the saints' Lives contained in Ælfrics Catholic Homilies have not been considered in this article; the modern title would certainly suggest that they ought to be. Following an argument put forth by Malcolm Godden in his article ‘Experiments in Genre: The Saints' Lives in Ælfrics Catholic Homilies’ in Holy Men and Holy Women: Old English Prose Saints' Lives and Their Contexts, ed. P.E. Szarmach (New York, 1996), 261-87, however, I would argue that later in his career, Ælfric perceived important differences between homilies and vitae, and that it is to this latter category that his two versions of the Life of Martin belong, thus putting those manuscripts beyond the boundaries of this paper.

4. As D. Scragg notes (‘Vernacular Homilies and Prose Saints' Lives before Ælfric’, in Old English Prose: Basic Readings, ed. P. E. Szarmach [New York, 2000], 83 n. 34), Morris's XVI (The Blickling Homilies EETS Original Series 58, 63, 73 [London, 1874-80]) is a detached leaf of homily IV, and his XVII-XIX are properly XVI-XVIII. In other words, there are in fact only eighteen, and not nineteen homilies, as Morris thought.

5. Note the following passage: þonne sceal þæs middangeard endian [on þam sixta elddo] & þisse is þonne se mæsta dæl agangen, efne nigon hund wintra & lxxi. on þys geare (‘‘This world must end [in the sixth age] and this the greatest portion has elapsed even nine hundred and seventy-one years’’). Blickling Homilies XI fo.141. (ed. Morris, 119, trans. mine).

6. See R. Vleeskruyer, ed., The Life of St Chad: An Old English Homily (Amsterdam, 1953), p. 56; H. Schabram, Superbia: Studia zum altenglischen Wortschatz, vol. 1 (Munich, 1965), p. 75. Quoted in M. Clayton, ‘Homilies and Preaching in Anglo-Saxon England‘, Peritia 4 (1985), repr. in and cited from Old English Prose: Basic Readings, 167 and n. 60.

7. Clemoes, P., review of The Blickling Homilies, ed. Willard, Medium Ævum 31 (1962), 61.

8. Blickling Homilies X (ed. Morris, 107, trans. mine)

9. Blickling Homilies VI (ed. Morris, 41 and 43, trans. mine).

10. Blickling Homilies VI (ed. Morris, 43, trans. mine).

11. For example, ‘The Birth of John the Baptist’: Men þa leofestan, her us manaþ & mynegaþ on þissum bocum & on þissum halgum gewrite, be þisse halgantide weorþunga þe we nu todæg mærsian sceolan & weorþian. (‘‘Dearest men, we are here admonished and reminded in these books & in these holy Scriptures of the observance of this holy season which we ought today to celebrate and observe.’’ ed. Morris, p. 161, trans. mine). ‘Peter and Paul’: Men ða leofestan, weorðian we on ðissum andweardan dæge Sancte Petres Cristes apostola ealdormannes þrowingtide. (‘Dearest men, let us on this present day celebrate the passiontide of Peter, the chief of Christs apostles.’ ed. Morris, 171, trans. mine).

12. Contrast Ælfrics later saints' Lives, which often begin with formulae such as: ‘x wæs gehaten sum halig godes þegn or x hatte sum halig godes þegn.’

13. M. Clayton, ‘Homiliaries and Preaching’, 170.

14. M. McC. Gatch, Preaching and Theology in Anglo-Saxon England: Ælfric and Wulfstan (Toronto, 1977).

15. É. Ó Carragáin, ‘How Did the Vercelli Collector Interpret "The Dream of the Rood"?’, in Studies in English Language and Early Literature in Honor of Paul Christopherson, ed, P. M. Tilling (Coleraine, 1981), 63-104.

16. É. Ó Carragáin, ibid. and ‘Rome, Ruthwell, Vercelli: "The Dream of the Rood" and the Italian Connection’, in Vercelli Tra Oriente Ed Occidente Tra Tarda Antichitá E Medioevo, ed. V. Corazza (Vercelli, 1997), pp. 59-105, esp. 87-97.

17. Vercelli Homilies XVI.192-5 (The Vercelli Homilies and Related Texts, EETS Original Series 300 [Oxford, 1992], ed. D. Scragg, 274, trans. mine)

18. K. Sisam, ‘Marginalia in the Vercelli Book’, in his Studies in the History of Old English Literature (Oxford, 1953), 118.

19. See the Catalogue of Irish Manuscripts in the Royal Irish Academy (Dublin and London, 1926-70), 3379-3404.

20. Leabhar Breac: The Speckled Book, Otherwise Styled Leabhar Mór Dúna Doighre: The Great Book of Dún Doighre, facsimile edition (Dublin, 1872), II. p. ix.

21. Consider the fate of Ælfric's works, which within his own lifetime were assimilated into collections with exactly the kind of unorthodox and non-authoritative texts against which he had rallied.

22. This in itself would not constitute sufficient evidence of a clerical audience, since it, like the Old English ‘Men þa leofestan’ could be a formulaic phrase marking the homiletic genre, as opposed to a literal address, and applied to mixed audiences as well as the purely clerical.

23. Passions and Homilies 6370-74, ed. Atkinson, trans. mine. Where deemed suitable, all Leabhar Breac quotations and translations are taken from The Passions and Homilies from Leabhar Breac: Text, Translation and Glossary, ed. and trans. R. Atkinson (Dublin, 1887). This is a somewhat confusing edition, however, which can provide a misleading representation of the manuscript. For this reason, the RIA facsimile edition (Leabhar Breac: The Speckled Book [Dublin, 1872]) will be referred to where it is thought helpful and necessary.

24. Leabhar Breac (Dublin, 1872), p. 68, col. 2. (cf. Atkinson, Passions and Homilies 5946ff.). Transcription, italics and trans. my own.

25. Leabhar Breac (Dublin, 1872) p. 69, col. 1-2. (cf. Atkinson, Passions and Homilies 5990ff.). Transcription, italics and trans. my own.

26. F. Mac Donncha, ‘Medieval Irish Homilies’, in Biblical Studies: The Medieval Irish Contribution, ed. M. McNamara (Dublin, 1979), 68.

27. Passions and Homilies 6513-15, ed. and trans. Atkinson.

28. F. Mac Donncha, Medieval Irish Homilies, 68.

29. See T. Ó Concheanainn, ‘The Scribe of the Leabhar Breac’, Ériu 24 (1973), 64-79.

30. P. de Brún, Catalogue of Irish Manuscripts in the King's Inns Library, Dublin (Dublin, 1972), 20-21.

31. F. Mac Donncha, ‘Medieval Irish Homilies’, 68.