Abstract

Memories can be made visible on the landscape resulting from people’s commemorative decisions. Remembering is a thoroughly social and political process, a realm of contestation and controversy. The past tends to be constantly selected, filtered and restructured in terms set by the questions and necessities of the present. Hence each landscape can raise questions about the political aesthetics and organisational forms utilised in their construction, and about the inclusions and exclusions of social groups and modes of memory, which each permits.

The connection of the nature of ruins to the collective memory debate provides further opportunities to analyse the processes of landscape formation. Duncan and Duncan (2010, p.231) asserts that the landscape serves as a vast repository of symbolism, iconography and ideology, as symbols of order and social relationships, such as ruins, can be interpreted by those who know the language of built forms. Edensor (2005b, p.4) writes that ruins comprise human-made parts and parts that nature is taking back through overgrowth. Ruins have their own time, place, space and life. Diverse rates of decay mean that some spaces and objects are erased whilst others remain. These processes create a particularly dense and disorganised `temporal collage' of memory. Hence according to scholars such as Edensor (2005b, p.4) memory is narrated and conceived of as an unfolding succession of stories the produce a plenitude of fragmented stories, omitted memories, fantasies and inexplicable objects.

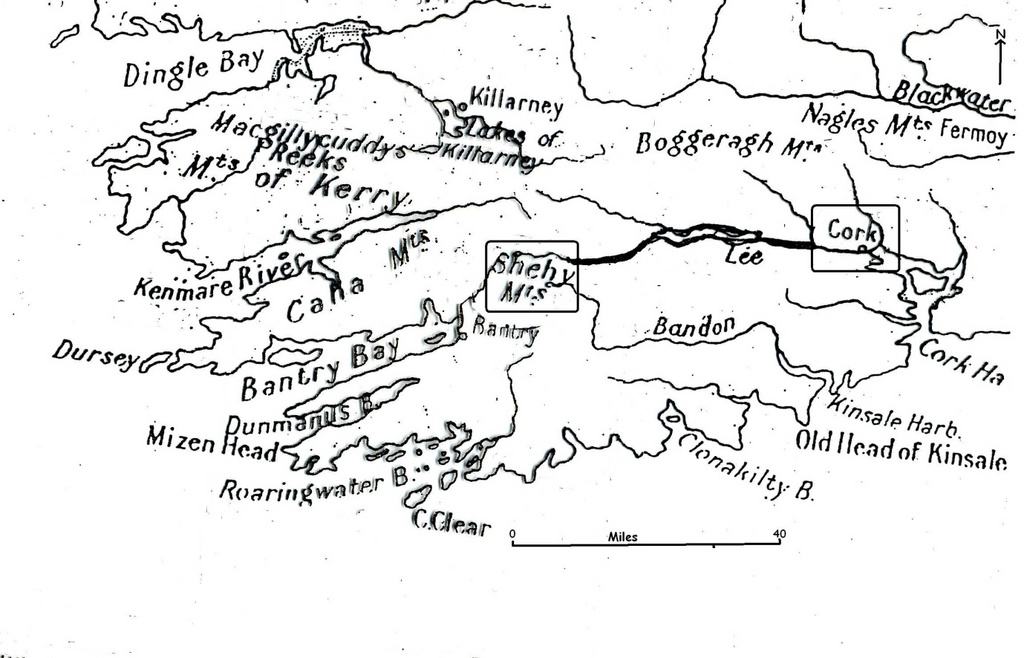

This paper investigates the question of the role of ruins in the production of memory in the landscape. In particular, it uses the pilgrimage site of Gougane Barra at the source of the river Lee, County Cork, Ireland to investigate meanings and the human experience associated with that meaning in ruins as part of the landscape.

“People can’t help making things, nature decays and rebuilds in the blink of an eye…and the surface of the planet’s so busy. These days it’s difficult to remember where I’ve come from. I might close my eyes and shards of past lie next to bits of half-memories and it’s impossible to tell whether I’ve featured in my life and what needs saving from it and what needs saving now…people cling to themselves and onto their machines and soon space is littered with centuries of debris”

— Walsh, 2010, p.45

Connecting the nature of ruins to the collective memory debate provides further opportunities to analyse the processes of landscape formation. In W.G. Hoskins' The Making of the English landscape (1955, p.14) he represents the countryside as an ancient place, filled with messages about the past. Cosgrove (1998, p.1) asserts that fundamental to the ‘message’ approach is the notion of landscape as a way of seeing, that the everyday landscape is typically a combination of art, artefact and nature, and the relationships between those categories are complex, multiple and layered. In a similar vein, Duncan and Duncan (2010, p.231) asserts that the landscape serves as a vast repository of symbolism, iconography and ideology, as symbols of order and social relationships, such as ruins, can be interpreted by those who know the language of built forms.

There are a myriad of symbolic meanings attached to ruins, which reveal the complexity of meanings of memory in the landscape. In his famous essay on the ruin, Georg Simmel (1965, p.259) wrote that "decay appears as nature's revenge for the spirit's having violated it by making a form in its own image". In a ruin, the edifice, the human-made part, and nature are one and inseparable; an edifice separated from its natural setting is no longer part of a ruin since it has lost its time, space and place. Ruins seem to be tangible memories ultimately made visible on the landscape resulting from people’s commemorative decisions. This article uses an intertextual approach as well as a set of ruins in Gougane Barra, a Christian pilgrimage site in west Cork, Ireland to investigate the meanings and human experience associated with ruins. Intertextuality provides a methodology to explore deeper into several of the meanings of memories that cross space and time.

Ogborn (1996, p.224) and Rose-Redwood et al (2008, p.162) argue that remembering as a thoroughly social and political process, a realm of contestation and controversy. The past tends to be constantly selected, filtered and restructured in terms set by the questions and necessities of the present. Edensor (2005b, p.15) writes that a ruin in a landscape raises questions about the political aesthetics and organisational forms utilised in its original construction, and about the inclusions and exclusions of social groups and modes of memory, which each permits.

Without historical information Crang & Travlou (2001, p.162), Hetzler (1988, p.51) and Lahusen (2006, p.736) contend that ruins still bear traces of the different people, processes and products bound up with memory. The stories amidst the ruins in places such as Gougane Barra produce many fragmented stories, omitted memories, fantasies and inexplicable objects. The stories are also infused with a host of intersecting temporalities, which collide and merge. Ruin time is significant in a ruin and according to Hetzler (1988, p.52) this time includes the time when it was first built, that is, the time when it was not a ruin, the time of its development as a ruin, the time of the fauna that may live in or on the ruin, the cosmological time of the land that supports it and is part of it and will take back to itself the man-made part eventually. As a result, narratives of a landscape feature, which present a history according to Hetzler (1988, p.52), can begin and end anywhere. History can be ‘up for grabs’, as it were, since the continuity between past, present, and future has been lost.

Scholars such as Edensor (2005b, p.4), Jackson (1980, p.91), Kansteiner (2002, p.179), Lahusen (2006, p.736), Rose-Redwood et al. (2008, p.161) and Simmel (1965, p.259) all make common assertions about the nature of ruins. They argue that ruins blur the boundaries of space and time, in a spatial sense as crumbling structures colonising their immediate surroundings and in a temporal sense articulating the overlayering of temporalities. All assert that ruins are sites in which the creation of new forms, orderings and aesthetics can materialize and that new forms release energy and creativity. Hence according to their perspectives new meanings can unfold within a modern ruin; a ruin can become for example a space of habitation, sociability, performance, exhibition, play, adventure, or ecological experiment. Ruins can provide ways of thinking about past cultures’ creativity, emotion, conflict, belief systems and community ideologies. With the ideas of the scholars at the start of this paragraph in mind, I wish to briefly address three aspects that deepen the understanding of ruins–mythic ideologies, the politics associated with ruins, and finally ruins and representation in Gougane Barra.

Ruins and mythic ideologies:

Fara (2000, p.407) argues that ruins on landscapes are re-interpreted by each generation of viewers; they can convey new meanings and new associations far from what the original users had in mind. It is largely through landscape and the artefacts that are part of the landscape that mythic images are experienced. Myths can anchor ruins as important to keep in the landscape. Similarly, the invention of myth becomes a method for using collective memory selectively by influencing certain bits of the national past, suppressing others, and elevating still others in an entirely functional way. Collective memory is not an inert and passive thing, but a field of activity in which past events are selected, reconstructed, maintained, modified and endowed with political meaning.

Gougane Barra, an Irish pilgrimage site in rural West Cork, links itself to Irish hagiography, the promotion and use of saints’ histories. In the only produced guidebook to the site entitled Life of St. Finbarr and published c.1901, Fr C.M. O’Brien tells of the legend of St Finbarr, the patron saint of the site and the Cork region. The saint is an important element of Gougane Barra’s grand narrative, but again its strength is based on the human upholding of the island site’s mythic past. O’Brien (c.1901, p.9) tells of St Finbarr being sent to the source of the Lee to exile a large serpent that dwelt in the lake. He subsequently drove the creature out and spent a time residing in the district. In time the early Christian ruins of the island site, the nature of which are unknown, became bound up with the life of St Finbarr and parts of his life and times were selected, reconstructed, maintained, modified, and endowed with new meaning to build a framework of new memories at Gougane Barra. It is unknown when the narrative was created or when the narrative began to be passed down. The site anchors itself in the oral traditions of St Finbarr. Through time, from the early Christian period to the seventeenth century, the passing down of mythology seemed to forge the ruins and environs of Gougane Barra as a site of Christian tradition (O’Brien, c.1901).

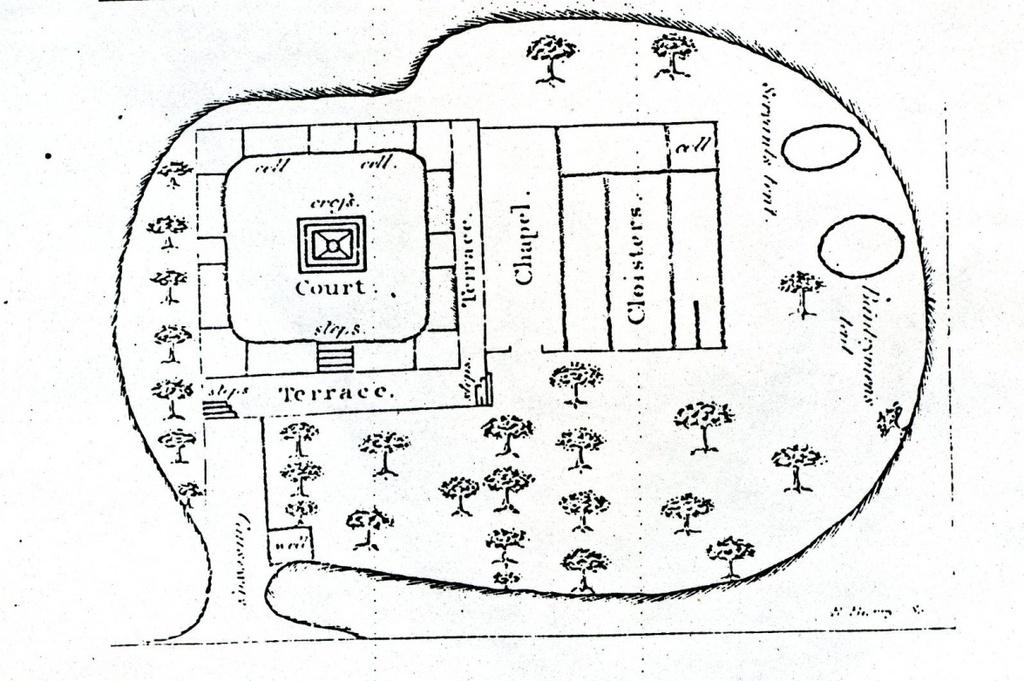

The advent of Catholic priest Fr Denis O’Mahony in the late seventeenth century added to that narrative when he introduced a memorial, a series of cells and gardens on the pilgrimage island. He chose to affirm the legend of St Finbarr and to physically enhance the symbolism of the island site. It could be argued that Fr O’Mahony built his monastery as part of a religious strategy to uphold, use and pass on its values to contemporary society. Fr O’Mahony brought his own mindset and education as priest and re-invented the folklore of St Finbarr in a tangible way by building a new living hermitage, and in turn created a living and working ruin to the saint.

However, all that remains in Gougane Barra are the cells and their enclosure wall—the gardens by Fr O’Mahony are gone and have fallen to the ravages of time. The extant ruins in Gougane Barra have become an unquestioned part of the social environment of the way of life in a region. They are embedded in the landscape and convey powerful cultural and ideological messages. They are the collective representations, which organise and structure people’s perceptions of time and space.

Mythic Gougane Barra seems to be a shifting construct: sometimes located in space, and at other times only in the mind. Each generation has made its own contribution to the myth of St. Finbarre. Authenticity is tied to an aged and weather-beaten look—signs of wear and tear remind one of the endangered states of the past and of notions of progress from a difficult past. In Gougane Barra, the enclosure wall has been revamped through time. Even new buildings have been added within the island pilgrimage site such as the early twentieth century oratory, which re-enforces the myth attached to the ruins.

The politics of memory:

Depictions of Gougane Barra are bound up with the politics of memory–that its memories were harnessed for political reasons. Landscape descriptions in Ireland in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, the time of Fr O’Mahony, are associated with forces of colonisation. There was a continuous rise in a new Protestant Ascendancy. The pattern of land holding was derived from Williamite campaigns of the late seventeenth century (McBride, 2001; McCormack, 1999 & O’Kane, 2004). The increase in Irish country house building, notable in the second quarter of the century, meant that patrons needed pictures, including landscapes, for their interiors. They wanted a record of their new houses and estates. Schematic mapping of features of terrain and their proximity to the Great House were carried out. The assessments of landscape were dependent on what the patron wanted. Charles Smith’s History of Cork in 1750 mentions hundreds of Great Houses and landlords (McBride, 2001; McCormack, 1999 & O’Kane, 2004).

The late eighteenth century was also a period when the interest in natural landscape phenomena heightened (Chaney, 1998; Trease, 1991). It arose from The Grand Tour, which was the traditional tour of Europe undertaken by mainly upper-class European young men of means. The custom flourished from about 1660 until the advent of large-scale rail transit in the 1840s, and had a standard itinerary associated with it. The primary value of the Grand Tour, it was believed, lay in the exposure both to the cultural legacy of classical antiquity and the Renaissance, and to the aristocratic and fashionable society of the European continent. In addition, it provided the only opportunity to view specific works of art, and possibly the only chance to hear certain music. A grand tour could last from several months to several years. It was commonly undertaken in the company of a knowledgeable guide or tutor. Once finished, recounting one's observations was considered an obligation to society at large to improve its outlook for the future; the Grand Tour flourished in this mindset (Chaney, 1998; Trease, 1991).

Descriptions of Gougane Barra first appear in Charles Smith’s History of Cork, which was published in 1750. He describes the natural features of county Cork as well as the topographical features of towns, villages, churches, key industries and demesnes across County Cork. In essence, he created memories of the landscape in published form, many of which were bought by Cork gentlemen who wished to be part of the project for status reasons. He also contributed to the power of this elite by providing information on them. Smith (1750) weaves Fr Denis O’Mahony’s story into the descriptive account of the Gougane Barra landscape. In his 1750 History of Cork (pp.192-194), Smith notes of Gougane Barra:

This retreat is esteemed one of the greatest curiosities in these parts; it lies in the remotest solitude imaginable, and is, in reality, a most elegant and romantic spot; its very aspect and situation betraying a place seemingly designed by nature for a recluse…This lake is environed by a stupendous amphitheatre of lofty hills, composed of perpendicular bleached rocks, in some places boldly hanging over the basin. In some crevices of the rocks, grow yews and ever-greens. This place since the time of St. Finbar, has been frequented by many devotees, as a place of pilgrimage; and to get to it; is little less than to perform one. In the island, are the ruins of a chapel with some small cells, a sacristy, chamber, kitchen and other conveniences erected by a late recluse [Father Denis O'Mahony] who lived a hermit, in this dreary spot, 28 years…Round part of the lake, is a pleasant green bank with a narrow causeway from it to the island. That part of the island unbuilt upon, Father O’Mahony converted into a garden, planted several fruit trees in it, with his own hand and made it a luxurious spot for a hermit. Opposite to this island, on the continent is his tomb, placed in a lofty little house. He was not buried in it till the year 1728.

Charles Smith writes about Fr O’Mahony creating a quasi private memorial space. One can view Fr O’Mahony not just as a priest but also an architect, landscape theorist, practical gardener and artist. O’Kane (2004, p.2) in her work on the elements that influenced demesne styles in the eighteenth century asserts that the human marks impressed on the landscape such as demesnes to small garden spots are a highly personalised view of the world as the creator viewed it and reveals personal attitudes towards philosophies and ideas of landscape. Thus, Fr O’Mahony created a composite work of art or as O’Kane (2004, p.1) alludes to, a landscape where “layered images, frames and views all add to augment the intellectual and sensual experience of place” in Gougane Barra.

Ruins, representation and invention:

The scale of the importance of ruins also seems to depend largely on a society’s response to them, in particular the immortalisation of ruins through the passing down of traditions, through various media systems. Schama (1995, p.1⁊) notes that ruins inspire a variety of responses. Images and representations constitute a key part in what Schama (1995, p.⁊) calls the ‘strata of memory’. The ruins of Gougane Barra remain active within contemporary meaning because the memory is kept alive indirectly through the medium of books, guide-books, memoirs, paintings, tourism and the changing practices of landscape design within the complex through the ages.

Artists and writers have communicated their thoughts and feelings, and hence have attempted to code, assimilate and depict Gougane Barra to the outside world, thus creating eyes for the viewer and new ways of seeing the West Cork site. Cosgrave (1998, p.2) and Read (1996, p.25) note that individual statements of landscapes turn into symbols for a universalised experience and reveal the search of the metaphorical associations of body and landscape. The spatialities and environmental relations of contemporary modern life are depicted.

The prospect of decaying grandeur is necessarily moving to those for whom the past itself consists of fragments awaiting reconstruction. An argument is presented by Schama (1995, p.396) that the greater the ruin, the greater the wonder of the onlooker. The sight of destruction gives a powerful impulse to preserve and record. It is itself conducive to a nostalgia, which can merge with concerns experienced by history. The very process of casting off the past generates nostalgia for its loss. With nostalgia for re-energized historical activity, the wonder is bound up with the human concern for the vanished or vanishing past.

Edensor (2005a, p. 829) argues that ruins provoke in the mind an urge to question their significance. Ruins challenge the viewer to make sense of them as they provoke a search for their meaning. From surveys and several hours of filmed interviews with visitors to the Gougane Barra pilgrimage island across a series of days in September 2009 and September 2011, many seem to come searching for something, something meaningful, a quest for understanding, quietness and escape and perhaps a journey inwards.

The idea of a timeless present is played out in George Petrie’s early nineteenth century painting of Gougane Barra. In the early nineteenth century, Anglo-Irish painters like Petrie developed approaches to landscape paintings deriving his style from a wide European tradition. Thomas Gainsborough looked back to Rubens while J.W. William Turner drew on his knowledge of Dutch marine painting, yet both went on to develop free and personal styles of painting. Irish landscape art tended to look to English models (Hamilton, 1997; Wolf, 2008).

George Petrie (1790-1866) was an important landscape painter of his day of the Irish landscape. He devoted himself to landscape painting in watercolours. In 1818 during a tour in the west of Ireland, he visited Clonmacnoise in the Irish midlands and copied the inscriptions on monuments and made drawings of over three hundred of them. From that point on he applied himself to the study of Irish history and antiquities. He began to explore people’s memories and native Irish cultural traditions as he found them in the historic fabric of old monuments and buildings in the four corners of Ireland (Murray, 2004).

Petrie’s appreciation of landscape was deeply indebted to William Wordsworth. He also had a constant awareness of the continuity between living folk art and antiquity. Petrie’s work explored the Irish space and landscape as an echo chamber informed by the lingering memories of native cultural traditions and antiquities. He read the Irish social landscape as a record of the country’s ancient Gaelic culture. Petrie proclaimed his cultural view of the Irish landscape as a repository for Irish antiquity (Murray, 2004).

Petrie’s work as a field officer with the Ordnance Survey of Ireland in the early nineteenth century was, according to Murray (2004, pp.39-40), an enormous salvage operation to collect and preserve the remains of Ireland’s native culture. He drew on the evidence of landscape, antiquities, cultural practices and ancient texts to penetrate Ireland’s lost antiquity. Petrie’s painting entitled Gougane Barra with the Hermitage of St FinBarr, painted in 1831 (one of two versions) attempts to put the viewer in the heart of the Shehy Mountains. George Petrie embodied the essence of the principles of the Romantic landscape aesthetic. Pilgrims/tourists seem dwarfed by awe-inspiring landscapes and give an increased interest and picturesque aspect to the scene.

There tends to be a sense of nostalgia to George Petrie’s work, the search for a lost past or memory. Petrie’s Gougane Barra captures a moment depicting a magnificent sky, shifting clouds, a veil of mist and a beam of sunlight breaking through. The light falls perpendicularly as if from heaven lighting up, and highlighting the ruins of the old Christian pilgrimage island, part of Ireland’s cultural identity. Petrie constructs a biography of Gougane Barra as a place where religious themes are significant. In my own observing of the painting, the ruins exist in the middle ground. The edgy architecture of the ruins to the viewer appear to be seen as signs of cultural life. The shafts of light through the clouds root the ruins in the middle ground of the landscape painting. In the background are distant mountains and peaks. High above these stretches a bank of clouds. The scenic excerpt is dominated by the deep space of a vista, prompting us to wonder what lies beyond. The artist compels the individual viewer to assume a very personal standpoint with respect to the implied world view. There is sense of solitude and romantic melancholy about Petrie’s work. There is a diversity of shades in the landscape, a depth given. The shadows make the sense of landscape depicted. The special qualities of weather are shown.

Ruins are open to interpretation. They present the unexpected and multiply the readings of place. Murray (2004, p.147) in his reading of the painting argues that George Petrie links the physical landscape to external phenomena. The meeting of the ruins, sky, the Shehy Mountains, the lonely lake and the shoreline of the lake are seen clearly, all contrasting with the small human figures shown in the foreground. There are stark contrasts of light and dark, which convey a feeling of eeriness, a wilderness and a powerful landscape carved out and protected by nature. There is intense emotion on the painter’s behalf aiming perhaps to disturb the viewer (Murray, 2004, p.147).

As depicted by George Petrie, a magical quality is created. As a result, according to Jackson (1980, p.32), a quality such as this connects to history enabling people to connect and even re-connect to one another through a sense of belonging. Ruins can draw on imagination and memories, ruins can provide intertextual resonances and can draw and interweave narratives from various eras of a site’s past through stories, myths, legends, rituals, and a feel of mystery. Ruins seem to create a kind of poetic landscape of monuments with links to some form of celebration of the living past and present. Prown et al. (1992, p.xiv) assert the concentration of multiple interpretative approaches and methodologies enlarges the understanding of other times and places. Those approaches in turn combine to create for a site an apparently strong sense of place, emotional attachment and identity.

Ruins and photography:

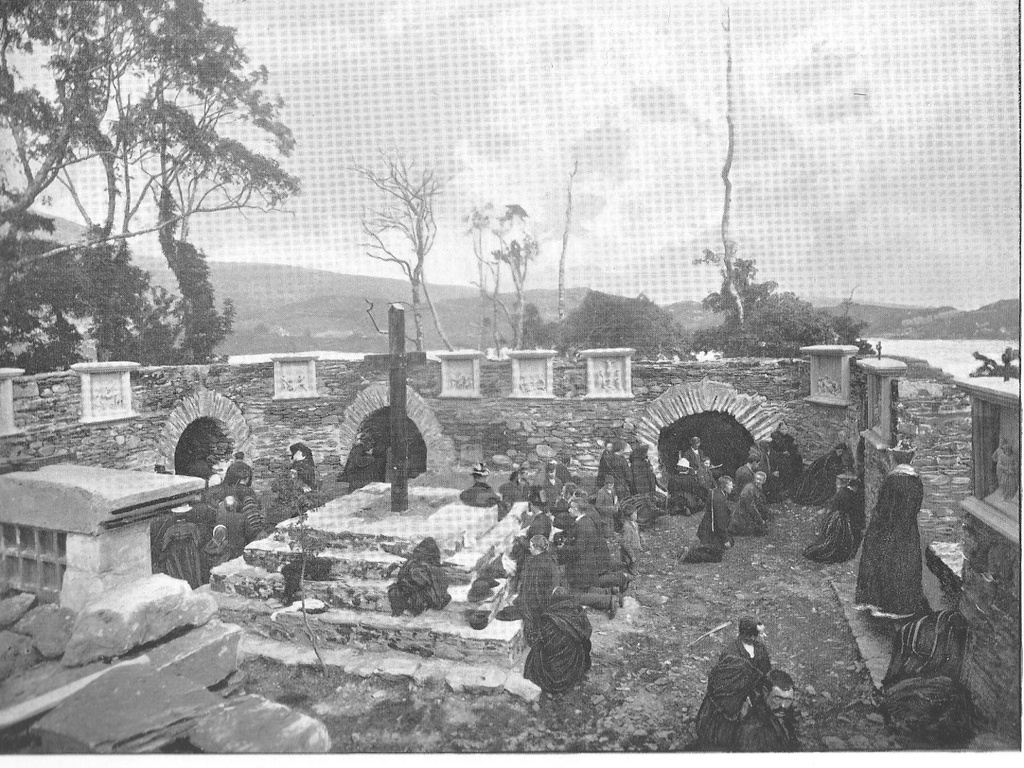

The paintings of the nineteenth century transform into postcards of Gougane Barra in the early twentieth century. These mnemonic images now present the ruins as a site of a genteel tourist space. A site of relaxation, enjoyment and even exoticism is presented. Hoelscher (1998, p.548 & 2007, p.195) emphasises the heavy visual bias of photographs and their additions to collective remembering. Photographs can be disseminated to a mass audience. Photographs are technologies of remembrance through which people construct the past and give memory as Hoelscher (2007, p.195) notes its ‘texture’. To Hoelscher (1998, p. 548 & 2007, p. 195) and Siggins (1999, p.115), no technology or media is more associated with memory than the camera image, especially the photograph. Visual imagery closes the gap between primary experience and secondary witnessing. It stands in for the larger event or person it is asked to represent. Memory demands an image. Image has texture, which contains both tactile and emotional dimensions. Hence memories are shared, produced and given meaning.

To Hoelscher (1998, p. 548 & 2007, p. 195), photographs can freeze time and appear to hold memory in place as they provide an immediately accessible vehicle for collective remembrance. They are strong memory freeze frames, as memory is forever transient, forever in flux. Photographs can provide the best evidence that something happened, a record of the ‘real’. Images of Gougane Barra represent the photographer’s response to the landscape at the very least and are an interpretation of an event that deserves attention. A set of photographs survive, which capture human interaction with the pilgrimage cell ruins (Baylis, 2007; Hoelscher, 1998 & 2007; Siggins, 1999). In late Victorian times, according to Baylis (2007, p.77) postcards attempted to demonstrate the importance of landscape imagery for the historical-geographical interpretation of social ideologies, of individual meaning, and of the complex web of power relations. There was a critical engagement with photographs not as pictures or documents but as social texts, as a discursive medium.

Hoelscher (1998, pp.548-570) notes three ideas revolving around landscape and photography. Firstly, photographic views were part of a more general Victorian search for order during a period of radical social and economic unrest. They reflected an ideology of human control over nature in their creation of a new, middle-class, post-frontier space. Nature became picturesque scenery and serviceable for mass-produced inspiration. Secondly, nature's scenic transformation was accomplished by photography, a superb vehicle of cultural mythology. The medium of photography is uniquely positioned to naturalize cultural constructions. Complex ideas of progress, development, and regional transformation maybe presented as laws of nature, as in controvertible facts. Thirdly, photography's apparent transcription of reality proved to be an immensely valuable asset for one’s enterprise in particular tourism. Pleasure travel expanded significantly in the late nineteenth century to include the emerging middle classes. Larger audiences also engaged with photography, many of whom were tourists.

Baylis (2007, p.77) asserts that acquiring photographs in Victorian times seemed to give shape to travel as it informed what the viewer should see, how it should be seen, and when it should be seen, all in a matter-of-fact and seemingly ‘unmediated’ way. Travel photographs became one component of a cycle that united itineraries, representations, and the landscape itself. Hence the photographs of Gougane Barra in the early twentieth century are new ways of seeing and experiencing landscape, which are themselves historically and geographically contingent.

The Gougane Barra photographs are the work of William Laurence and his firm. The photographs embody most of the tensions and contradictions that are ingredients of this critical union of landscape, photography, and tourism. The man who took all the photographs, other than studio portraits, for the firm of William Lawrence from the late 1870s to 1914 was Dublin man Robert French. He took at least 40,000 photographs over approximately 30 years. During that time railways criss-crossed the land. Irish cities in particular were being transformed. Public transport was being introduced. Dublin, Cork and Belfast were expanding rapidly. Whole new suburbs were built. Ireland followed Victorian fashions and trends (Horgan, 2002, p.30).

William Lawrence developed lecture sets covering each city, county and beauty spot, portraits of priests, prelates and politicians, churches, jails and prisons, scenes of Irish life and character, comic sketches of Irish life and character. They came in albums, as magic lantern slides, and stereoscopic views. There were postcards by the thousands. Most of them hand-coloured as were the other views which came in elaborate frames (Baylis, 2007; Breathnach, 2007).

Horgan (2002, p30) notes that view photography for Lawrence became a principal visual medium to naturalize and celebrate spaces such as Gougane Barra. Lawrence’s photographs reflected and promoted a late nineteenth-century tourist aesthetic based on the belief that nature could be exploited not only for its extractive resources but also for its recreational and restorative potential. Most often Lawrence achieved the picturesque by peopling the landscape with well-dressed Victorian men, women and children. It was the artifice of the picture, its staged and ‘picturesque’ quality that, though appearing to be ‘natural’, also suggested ultimate human control over nature. The capturing of the visibility of nature by the use of the camera was equally about asserting a stake in the Irish landscape. The appeal of rural Ireland represented the assurance of uncharted terrain and the recovery of a pre-conquest identity of language, culture and nation. The countryside was to be rendered not only as an unworked but also as a scenic and visually oriented playground for the burgeoning urban middle classes. Tourists were seen as people whose only function in the landscape is to look at and admire its beauty and claim it as their own (Baylis, 2007; Breathnach, 2007; Horgan, 2002). The key image of Lawrence’s pictures of Gougane Barra is of tourists praying in the centre of Fr O’Mahony’s ruins. The position of viewers is both inward looking and purposeful. The ruins are both authentic and primitive. The image pays homage to the act of pilgrimage but is also reminiscent of Bartlett’s nineteenth century paintings of Gougane Barra, especially the views used.

Conclusions:

To conclude, ruins help the viewer to memorialize, reinforce and even substitute for their experiences of the events that led the structure to enter into a ruinous condition. Hence, as ruins are part of the landscape, they are also part of the active processes of remembering. This paper focuses on the creation of a site biography of ruins and exploring the raison d’être of those who created them and who interacted with them through painting and photographing them. Those elements underline the importance of monuments, as in Gougane Barra in anchoring the collective memory of the community. The Christian ruins at Gougane Barra are presented through oral traditions, literature and media systems as bound up with something ancient, sacred, soulful and purposeful–something motivating and ambitious. It’s as if the ruins provide the landscape with a voice. For the pilgrim, the ruins create a landscape of living encounters, experiences and connections.

- Bartlett, W.H., 1840, The Scenery and Antiquities of Ireland, George Virtue Press, London.

- Bell, S., 1996, Elements of Visual Design in the Landscape, E. & F.N. Spon Publisher, UK.

- Baylis, G., 2007, “Technologies and Cultures: Robert J. Welch’s Western Landscapes, 1895-1914”, in Breathnach, C. (ed.), Framing the West, Images of Rural Ireland, 1891-1920, Irish Academic Press, Dublin, pages 77-98.

- Breathnach, C. (ed.) 2007, Framing the West, Images of Rural Ireland, Irish Academic Press, Dublin.

- Chaney, E., 1998, The Evolution of the Grand Tour: Anglo-Italian Cultural Relations since the Renaissance, Frank Cass Publication, London.

- Cosgrove, D., 1998, Social Formation and Symbolic Landscape, The University of Wisconsin Press, USA.

- Crang, M. & Travlou, P.S., 2001, “The city and topologies of memory”, Environment and Planning D: Society and Space, vol. 19, pages 161-177.

- Duncan, N. & Duncan, J., 2010, “Doing Landscape”, in Delyser, D., Herbert, S., Aitken, S., Crang, M. & McDowell, L. (eds.), The Sage Handbook of Qualitative Geography, Sage Publications, London, pages 202-223.

- Edensor, T., 2005a, “The ghosts of industrial ruins: ordering and disordering memory in excessive space”, Environment and Planning D: Society and Space, vol.23, pages 829-849.

- Edensor, T., 2005b, Industrial Ruins, Space, Aesthetics and Materiality, Berg Press, Oxford.

- Fara, P., 2000, “Isaac Newton lived here: sites of memory and scientific heritage”, The British Journal for the History of Science, vol. 33, no. 4, pages 407-426.

- Hamilton, J., 1997, Turner– A Life, Hodder and Stoughton, London.

- Hetzler, F.M., 1988, “Ruin time and ruins”, Leonardo, vol. 21, no. 1, pages 51-55.

- Hoelscher, S., 1998, “The photographic construction of tourist space in Victorian America”, Geographical Review, vol. 88, no. 4, pages 548-570.

- Hoelscher, S, 2007, “Angels of memory, photography and haunting in Guatemala City”, Geojournal, vol. 73, pages 195-217.

- Horgan, D., 2002, The Victorian Visitor in Ireland, Irish Tourism, 1840-1910, Imagimedia, Cork.

- Hoskins, W.G., 1955, The Making of the English landscape, Hodder Press, UK.

- Hurley, P., 1892, “Notes on Gougane Barra”, Journal of the Cork Historical and Archaeological Society, 1892, p.193.

- Jackson, J.B., 1980, The Necessity of Ruins, University of Massachusetts Press, USA,

- Jackson, J.B., 1984, Discovering the Vernacular Landscape, Yale University Press, USA.

- Jackson, J.B., 1994, A Sense of Place, a Sense of Time, Yale University, USA.

- Kansteiner, W., 2002, “Finding meaning in memory: A methodological critique of collective memory studies”, History and Theory, vol. 41, no. 2, pages 179-197.

- Lahusen, T., 2006, “Decay or endurance? The ruins of Socialism”, Slavic Review, vol. 65, no. 4, pages 736-746.

- McBride, I., 2001, History and Memory in Modern Ireland, Cambridge University Press, UK.

- McCormack, W.J. (Ed.), 1999, The Blackwell Companion to Modern Irish Culture, Blackwell Publishers, UK.

- Murray, P, 2004, George Petrie (1790-1866), The Rediscovery of Ireland’s Past, Crawford Art Gallery, Cork with Gandon Editions, Kinsale, Co. Cork.

- Prown, J.D., 1992, “Introduction”, in Prown, J.D., Anderson, N.K, Cronon, W., Dippie, B.W., Sandweiss, M.A., Schoelwer, S.P., Lamar, H., Discovered Lands, Invented Pasts, Transforming Visions of the American West, Yale University Press, USA, pages x-xv.

- O’Brien, C.M., c.1901, Life of St. Finbarr, Reprint of Killarney Printing Works, Ltd., Killarney.

- O’Kane, F., 2004, Landscape design in Eighteenth Century Ireland, Cork University Press, Cork.

- Ogborn, M., 1996, “History, memory and the politics of landscape and space: work in historical geography from autumn 1994 to autumn 1995”, Progress of Human Geography, vol. 20, no. 2, pages 222-229.

- Read, P., 1996, “Remembering dead places”, The Public Historian, vol. 18, no. 2, pages 25-40.

- Rose-Redwood, R, Alderman, D., Azaryahu, M., 2008, “Collective memory and the politics of urban space: An introduction”, GeoJournal, vol. 73, pages 161-164.

- Schama, S., 1995, Landscape and Memory, Vintage Books, New York.

- Siggins, B., 1999, “Robert French and the Lawrence Collection”, Dublin Historical Record, vol. 52, no. 2, pages 115-125.

- Simmel, G., 1965, "The Ruin," in Kurt H. Wolff (ed.), Essays on Sociology, Philosophy, and Aesthetics, New York, USA, page 259.

- Smith, C., 1750, History of Cork, Cork.

- Trease, G., 1991, The Grand Tour, Yale University Press, USA.

- Walsh, E., 2010, Penelope, Nick Hen Books Ltd., London.

- Wolf, N., 2008, Landscape Painting, Taschen Publishing, London.