Apprehension, uncertainty, waiting, expectation, fear of surprise, do a patient more harm than any exertion. (Florence Nightingale)

Parental concern about child development

If you want to know if a pre-school child is developing normally just ask their parents whether they are concerned…right? Yes, this approach is regularly used by health care professionals who work with parents to assess normal growth and development as part of preventative child health services. However, this approach is not always successful and parents may be reluctant to express their concerns to a doctor or nurse. So, do we know what triggers parents to go and seek help about a growth or development concern? Well no, because most of the studies already conducted have been about trying to measure parents concern about child growth and development.

Assessing normal child development is challenging not least because children grow rapidly and often in spurts. Developmental delays are relatively common but not all of them indicate developmental disabilities. However, it is important for any delays in growth or development to be assessed so that any deviations from normal development are identified promptly and treated if appropriate. Referral to early intervention services is most effective if it happens early and ideally before a child goes to school. The consequences of late identification of developmental delay are as follows:

- Unfavourable effect on child health and behaviour

- Adverse impact on future academic and social functioning

- Parental distress

- Impaired family functioning

- Economic costs for society

These consequences highlight the need to understand how parents’ concerns about child development problems can be identified and expressed as effectively and efficiently as possible.

Study design

In this study I wanted to understand how parents made sense of their concerns about their child’s growth and development problems by exploring their experiences. Using a methodology called Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis, developed primarily by Jonathan Smith, helped me to design a study where I tried to make sense of parents’ experiences. This entailed moving beyond describing the experiences and endeavouring instead to interpret them. I interviewed parents of 15 children who had various child growth and development concerns. The purpose was to listen to them describe their experiences of trying to make sense of a concern that there might be something wrong with their child, through to seeking help from a Health Care Professional. One theme discovered between parents feeling “uncertainty – a little bit not sure” and going to “Get the problem checked out” was called “Triggers to action”.

Triggers to action

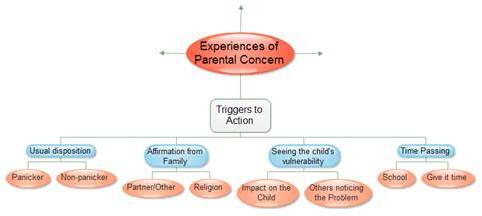

Parents rarely described just one trigger that prompted them to take action in addressing their child’s concern formally with a doctor or public health nurse. More often than not there was a combination of themes: ‘Usual disposition – to panic or not to panic’; ‘Affirmation from Family’; ‘Seeing the Child’s Vulnerability’ and ‘Time Passing’ (see Figure 1 below).

The themes identified within “triggers to action” will be further explained in the following sections.

Usual disposition – to panic or not to panic

“Usual disposition” was identified as a trigger for action for parents. This finding described parents who were panicking and not panicking as motivations or triggers for action to go and seek help; a finding not found previously in studies on parental concern. Parents described in detail their usual disposition with reference to how they reacted generally when dealing with child health-related concerns. Their accounts were particularly insightful in understanding how quickly they acted on concerns. There were parents that had concerns yet did not act quickly on them. Some of these parents described themselves as the non-panickers and depicted themselves as quite laid back. They were happy to ‘let nature take its course’ within reason, or ‘let them grow out of it’. There were other parents who were quite proactive in their actions and just went to ‘check it out’ with a health care professional when they had a doubt of any kind. Alternatively, some parents adopted both approaches depending on the nature of the concern. One parent’s account of going into a complete panic when she thought her daughter had a squint was notably different to her more measured reaction in response to the child’s speech and language concerns. This finding suggests that parents’ fears can be heightened by the visible nature of an observable problem requiring immediate assessment by an appropriate healthcare professional. Parental anxiety and assertiveness were previously found to prompt help-seeking in child illness scenarios. However my findings in relation to parents’ usual disposition have important clinical implications. Healthcare professionals should broaden their assessments in preventative healthcare settings to include identification of those who may be more likely to adopt ‘a wait and see’ approach. These parents may require more probing of any potential child development concerns.

Affirmation from family

Family and friends were found to be triggers for action to seek help, a finding not previously discovered in children with developmental concerns. Family affirmation in the form of them seeing what the parent could see with the child seemed to give strength to parents to go to a doctor or public health nurse and express their concern. At other times family or friends explicitly said that the parent should go and ‘check it out’. Support from family and friends were also valued by parents. This finding supports previous studies where social supports were found to reduce uncertainty and validate parental concern in instances where there were fears about childhood illness. There was also evidence from previous studies of other people being direct with parents relating to children with faltering growth. However, in that context it implied criticism of parents about their parenting ability. In contrast in my study it is possible that other people in the non-panicking parents’ circle were simply drawing attention to the problem by just noticing the child’s problem or advocating explicitly for a more proactive response to get the child’s problem checked out. Perhaps these family and friends were familiar with the non-panicking parents’ usual disposition and believed this problem with the child was one that required more immediate action.

Seeing the child’s vulnerability

It seems inevitable that the vulnerability of the child would be identified as a trigger for action because parents invariably act in the best interests of dependent small children. Findings indicated that parents were cognisant of the physical and emotional impact of the growth or development problem on the child but it rarely was a sole trigger for action. Although one mother was keen to get her daughter’s speech and language problem addressed before she went to school because she was worried about others calling her ‘a baby’. Parental worries about trying to protect their children from being teased at school were found previously, albeit in older children with Developmental Coordination Disorder and also in those who were overweight. The findings from the current study point to the need for doctors and public health nurses to explore parents’ perceptions of the impact of the child growth or development concern on the child, and their perceptions regarding school readiness. This may shed further light on the nature of the child development problem and trigger expression of concern.

Time passing

Whilst the passing of time influenced parents’ actions they did not describe it explicitly as such. Instead parents alluded to time passing when they spoke about how fast their children were growing or developing. It is widely acknowledged that young children grow and develop quickly. Caring for young children is demanding for parents and sometimes parents are forced to confront or assess what is happening developmentally. One mother captured this best when she spoke about being ‘aware’ of her son’s developmental problems but when her older daughter commented about him ‘losing his words’ she said children sometimes are good to point out the obvious. She said she had been too busy with all the other things going on in their lives to see. It is almost like time passing is variable in speed and parents sometimes may think they have more time to deal with an issue and then a deadline like starting school looms which triggers action.

Conclusion and implications for practice

Triggers to action as a combination of factors were not previously found in studies relating to parental concern about child growth and development. Given the complexity of child growth and development it is unsurprising that triggers to action would be a multifaceted theme influenced by the broad determinants of health. Therefore, this finding is very important in terms of understanding what influences parents to decide to go and get their child’s problem checked out. In terms of implications for clinical practice it implies that there is need for doctors and public health nurses to adopt a model of care that incorporates the physical, psychological and social determinants of health. This will ensure the holistic needs of the family, beyond a mere disease/disability dimension are appropriately assessed. Preventative child health services rely on close collaboration between health care professionals and parents, to ensure any deviations from normal growth and development are promptly identified and addressed. The findings from this study show that assumptions should not be made about the factors that trigger concerned parents to act.

Thanks to my supervisors Professor Eileen Savage, Chair of Nursing and Head of the School of Nursing and Midwifery and Dr. Rhona O’Connell.