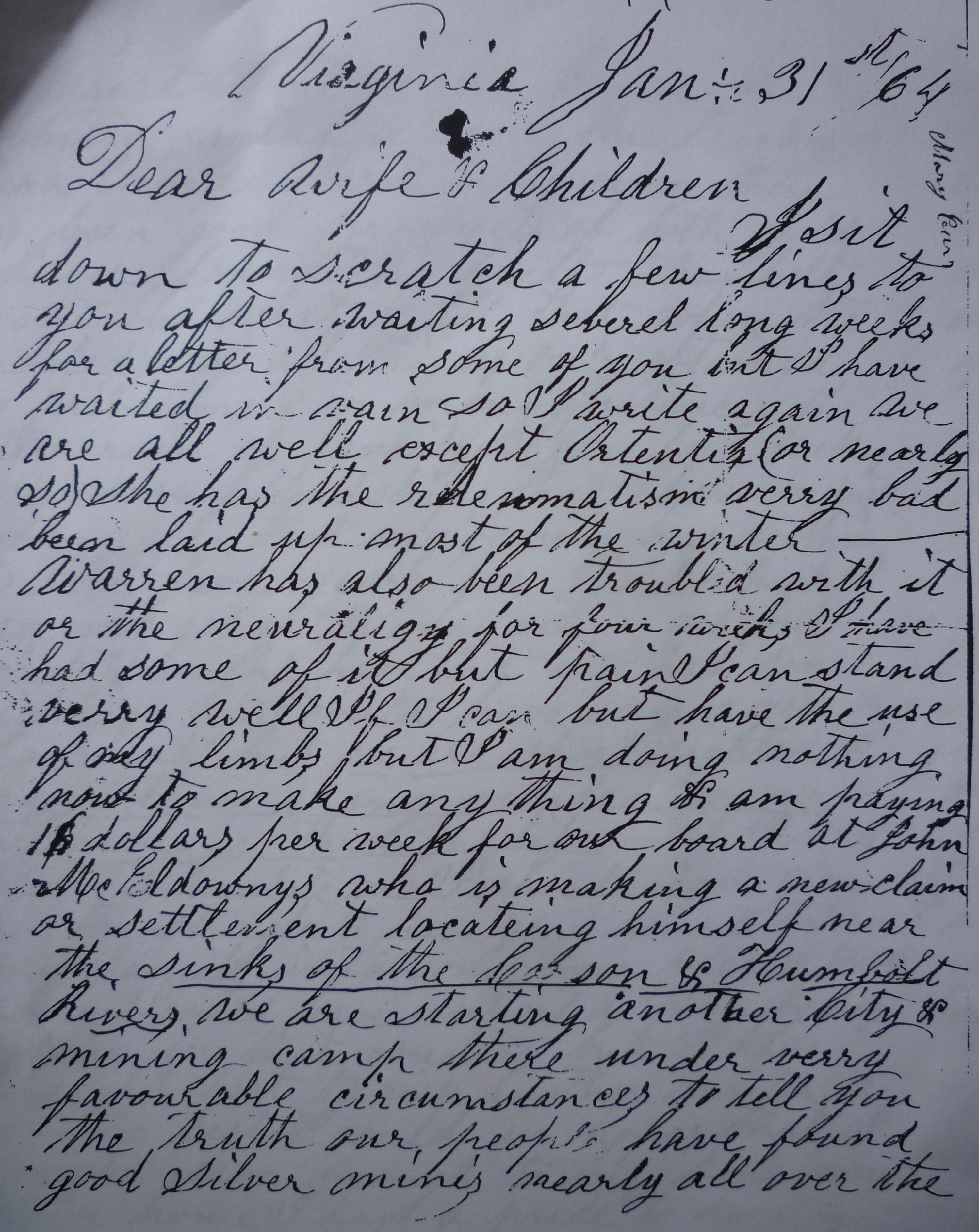

‘Oh those long months without a word from home, my neighbours get letters but I none’ - Chauncey Carr Jr (Letter to his family, 31 January 1864, Carr Family Letters).

Past communications

Recent economic woes in Ireland mean many are once again emigrating in search of jobs. Emigration can be an emotional event for the emigrant, and those they leave behind. However, this generation will experience emigration differently to any previous generation. The advent of the internet and webcam services means that there are no longer any communication delays between emigrants and their friends and family because of vast geographical distances. It is easy to forget how recent these changes have been. In 1873 Michael Flanaghan an emigrant in California, wrote to his family home in Ireland marvelling at a photograph of his brother; ‘It is a most useful art this photographing by which one can send from one end of the world to the other a pretty correct representation without writing a word about it’ (M. Flanaghan, 5 July 1873, Flanaghan family letters, Miller Collection, University of Missouri). Our own technological advances have transformed emigrant’s interactions with their families at home, allowing people to see and speak to one another instantaneously, a communication revolution which has reduced the humble letter, and indeed the material photograph, to relics of a bygone era.

While researching my dissertation on Irish miners, titled Wandering Labourers: The Irish and Mining throughout the United States, 1845-1920, I found one of the richest veins of information was migrant letters. Within these we can find fascinating details of the lives and thoughts of these migrants, their relations, and their friends. The focus of this article is on these letters from miners, particularly Irish miners, in the nineteenth century. Over this topic hovers the questions, how will future researchers grapple with new technologies as a source of information, and will digitisation render the historian’s task more difficult if no physical trace is left of contact between loved ones?

1875, Crawford Art Gallery, Cork).

A global network

In the nineteenth century, the Irish Diaspora was a global phenomenon centred on the United States and the British Empire. Letters and newspapers were the global communication networks of the nineteenth century. As with the internet, not everyone could participate in this medium. The barrier to access in the nineteenth century was illiteracy, a common problem for many emigrants. For those at home in Ireland it was less of a problem, as they could find someone locally to read the letters sent to them, often a young person in school (see Figure 1) or a priest. As public education spread across Ireland and letter writing became more popular, it allowed more migrants to remain in contact with each other and their families throughout the world. This communication network was especially important for miners. A highly mobile transitory workforce, they depended on information about mining opportunities elsewhere with better wages. Examples of this global network in action are the letters between the four Flanaghan brothers; Michael (quoted above), Patrick, Nicholas, and Richard. After hearing from Patrick that pay was high in Australia, Michael took the long trip in search of work and his brother. He noted; ‘…I was over a week on the diggings before I found Pat. One day I was winding my way amongst the barks and slabs which compose the township and I saw advancing before me a curious looking bushman and as I came closer and got a little nearer him I found I saw the face before but not until he put out his hand and began laughing did I fully recognise the man I was in search of... His appearance would nearly put one in mind of a Maori’ (M. Flanaghan, Brisbane, Queensland, to his uncle, 18 February 1865).

The brothers worked there for a time before joining the gold rush to New Zealand a few years later. Another brother, Nicholas, decided to forego mining and instead settle in Ohio, where he worked on a farm. He later told his brothers that, ‘…I was sorry for a while after I came to this country that I did not go to Australia but I got over that and now I like this country tip top and I intend to make my home in this country’(N. Flanaghan, 5 January 1869). After this he details the local wages ($1.48 a day) and ends with his assessment of the United States stating, ‘I think there is no better country than this for a man that would have a little capital’. Patrick Flanaghan led the way to California, much to the chagrin of his brother, Richard, back in London who was surprised to hear from Michael that Pat had moved on without informing them at home; ‘I felt a good deal disappointed that you told nothing of your plans or arrangements for the future...At first I could hardly credit it, as I thought he wuld [sic] not have undertaken such a step without letting someone at home know of it directly’ (R. Flanaghan, 20 August, 1870). Yet Richard tempered his letter towards the end, reviewing his brother’s decision he wrote, ‘I think he has done wisely as it is most undoubtedly a splendid country – far exceeding in many advantages any your [sic] Australian Colonies ’ (R. Flanaghan, 20 August, 1870). Many were not quite as enthusiastic about the United States. John Hall was a recent immigrant labouring in the coal fields of Pennsylvania, and when his sister asked for his impression of America he wrote the following back to her, ‘I do not like it at all...any person who can live at home at all had better stay there for in this country there is neither comfort nor pleasure’ (J. Hall, 27 November 1888,).

‘What wages do they pay in the shops in Manchester for a good workman at the anvil & what chance is there to get work’, Irishman James Williamson wrote bluntly to his brother John in England (James Williamson, 2 October 1850, Williamson family letters, Public Records Office of Northern Ireland). He was a Californian gold digger and was seeking a different occupation and a different home. Writers were not always as direct as James Williamson, and most appreciated any letters at all from people they knew. ‘There is nothing gives [sic] me greater pleasure than to get letters from my friends even if they are short ones’ wrote the Irish Bartholomew Colgan in Carson City, Nevada, to his fellow emigrant, Thomas Dunny in Illinois (B. Colgan, 13 June 1862 Dunny family letters, Schrier Collection, courtesy of Kerby Miller). The quote from Chauncey Carr Jr in the introduction and in Figure 2 demonstrates the desperate longing of migrants for letters from home. Letters were not always reliable; sometimes they were delayed, damaged, or even lost, ‘You need not be disappointed at not hearing from your friends at home. You see one of my own letters has miscarried and I have thro’ the Dead Letter, or Returning letter office [sic] a letter that Rick wrote to you when at home here last September twelve months’ (R. Flanaghan, 24 January 1867).

Both Patrick and Michael Flanaghan eventually settled in the Napa region of California. Three quick deaths in the family left the father alone back in Ireland and he pleaded for Michael to return home, ‘I would wish very much to see you before I die. If I thought you were married or had a family to provide for I would not ask you to come home’ (John Flanaghan, 7 April 1890). Michael dutifully returned home and continued to write to his brother Patrick who remained in California. In those letters Michael regretted his repatriation for many years, before eventually making peace with his decision in his old age. Before he made the final journey back to Ireland, he wrote the following lines:

This journey frightened me a little, but whether for good or ill I shall risk it anyways, if it ends well it will be fully as much consolation to me to see you as it will be you to see me again. Instead however, of the lad of seventeen years you saw last you will meet a grey old man of fifty (M. Flanaghan, 20 May 1890).

Printed letters

Historians find letters in many locations and collections but emigrant letters could also be found in newspapers, often as warnings. A letter, from the chief mate of a ship in California to his brother in Belfast, was reprinted in The Belfast News-Letter on 15 February 1850 as a guide to the jobs and wages in distant lands of the California gold rush, ‘An old friend of the captain's came on board the other day, and stated that in four months he had realized 9,000 dollars at the “diggings”’. These letters also existed as a warning to any prospective emigrants in Ireland. The migrant in the letter goes on to detail about the friends’ exploits, ‘He dined on shore that evening, brought his gold with him, got into a gambling house, and was cleared of every ounce of it’.

Some of these letters were humorous spoofs written in the same tone as emigrant letters, which indicates how common these letters were amongst the public. The Belfast Commercial Chronicle printed one such letter under the title ‘AN IRISHMAN’S LETTER FROM CALIFORNIA’ on 15 April 1850 from a ‘Terence Finnegan’ to ‘Biddy’ in Ireland. ‘Accushla, sarching [searching] for goold [gold]; but a body might as well look for new pitayies [potatoes] in Thriffalgar-square [Trafalgar Square]’. The piece continues to mock Irish accents throughout detailing the following pun as a humorous misunderstanding, ‘You may have read in the papers that the diggers goold [gold] in quartz [quarts]; but don't believe it, Biddy. I'll be on my oath none of them ever found a pint of it’. Terence ends the fake letter pleading Biddy to ask his friends to hold a raffle and send him the fare back to Ireland.

Bearer of bad news

In their letters, emigrants often asked for news and gossip about friends and family they have left behind or who had also emigrated. Often these replies must have made for difficult reading. After detailing the recent death of her four-year-old daughter from scarlet fever, Ellen Wogan continued her letter to her brother in the far West, ‘Dear Brother you would like to hear from all your old school-fellows. There is not one here that I know of they are all dead and scatered [sic] away’ (Ellen Wogan, 2 September 1870). Such news understandably caused migrants to despair at their lot in life,

‘I have mined so long I am hardly good for anything else’ wrote another Irishman, William Kennedy, and he continued:

Oh dear oh dear how I can look back and see all the old familiar places and faces and imagine myself back there a boy hen [boyeen?] going to school with my old School mates - bare foot running races on the green grass and wading in the Lagan in the afternoons coming from School. Oh dear oh dear those times will never come back to me (W. L. Kennedy, 3 February 1870, Kennedy family letters, Public Record Office of Northern Ireland).

Despite his melancholy turn he ended the letter determined that ‘I will see all the old places, once more before I quit this world’ (W. L. Kennedy, 3 February 1870). A long wait for a reply would often mean the worst, ‘I have not had a letter from home now - from any one of our family for more than a year - Isabella used to correspond with me regular untill [sic] lately and I fear very much either she has been very sick or is dead - the latter I fear’ (W. L. Kennedy, 3 February 1870).

The development of instantaneous global communication is a tremendous boon to emigrant networks, including the Irish Diaspora, and will change them in a myriad of different ways. Perhaps the most important of these changes is that recent emigrants need not face the terrible uncertainty earlier emigrants faced, and for that we can be grateful.

Thanks to my supervisor Dr. Andy Bielenberg, and to Professor Kerby Miller who generously granted me access to his collection of letters on my visit to the University of Missouri, Columbia.- Further Reading

- Conway, Alan, The Welsh in America: letters from the immigrants (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1961).

- Fitzpatrick, David, Oceans of consolation: personal accounts of Irish migration to Australia (Cork: Cork University Press, 1994).

- Miller, Kerby, Emigrants and Exiles: Ireland and the Irish Exodus to America (New york: Oxford University Press, 1985).