He would explain to his readers, they who lived in a country millions of miles from Belfast, that a people were outraged, deprived of hope, and so alone. (Sorj Chalandon, French journalist)

Introduction

The French and the Irish have for many years had a certain affinity and a distinctly positive regard for each other. It may well be that our shared history and Celtic ancestry, or common religion have helped to bring us together and to support each other. For centuries religious links have been forged by successive waves of missionaries who travelled from Ireland to the European continent to spread the faith. While these religious links may not today be as strong as they once were, there are still several extremely strong links between the two countries, for instance in the areas of culture, education or business. In recent times the creative talents of the writers James Joyce and Samuel Beckett and artists such as Walter Osborne, Roderic O’Conor and Eileen Gray have helped to establish and foster the bond between the two countries.

For well over a hundred years, news stories from and about Ireland have featured heavily in the pages of the French press. This was particularly pronounced during the early part of the twentieth century when Ireland was still under British rule. At that time attempts by Irish men and women to bring about Irish independence were written about, in great detail in a wide variety of French newspapers. This research project will look at the unique relationship that exists between Ireland and France through the work of a broad range of French journalists from different backgrounds and political perspectives who came to Ireland to report on specific events for the French press. It is hoped to be able to reveal why the strong links exist by examining the work of these French journalists.

Grand reporter

Much like the embedded journalists that we hear about today who cover America’s wars in Afghanistan and Iraq, the French journalists who travelled to Ireland during the early part of the twentieth century located themselves at the heart of the action. The French press created the term grand reporter to describe this new type of journalist, who would travel from place to place to report on major events around the world as they unfolded. Technological progress and improvements in various modes of transport meant that the grand reporter could travel almost anywhere in the world, even at very short notice. French journalists such as Joseph Kessel (1898-1979), Henri Béraud (1885-1958) and Simone Téry (1897-1967) embody this intrepid explorer better than anyone else. During the 1920s, 1930s and 1940s they travelled widely to report from the heart of conflicts in Europe, such as Ireland in the 1920s and Spain’s Civil War in the 1930s. Their reports from Ireland were often front page news on the different newspapers that they worked for. It would not be an exaggeration to say that for a number of years at the beginning of the twentieth century, Ireland was a major rallying point for the grands reporters on the journalistic pilgrimage around the world. They also travelled to other hot spots such as the Middle East, Russia and Africa to report on many of the major local and international conflicts at that time.

Reporting major events of Irish history in French newspapers

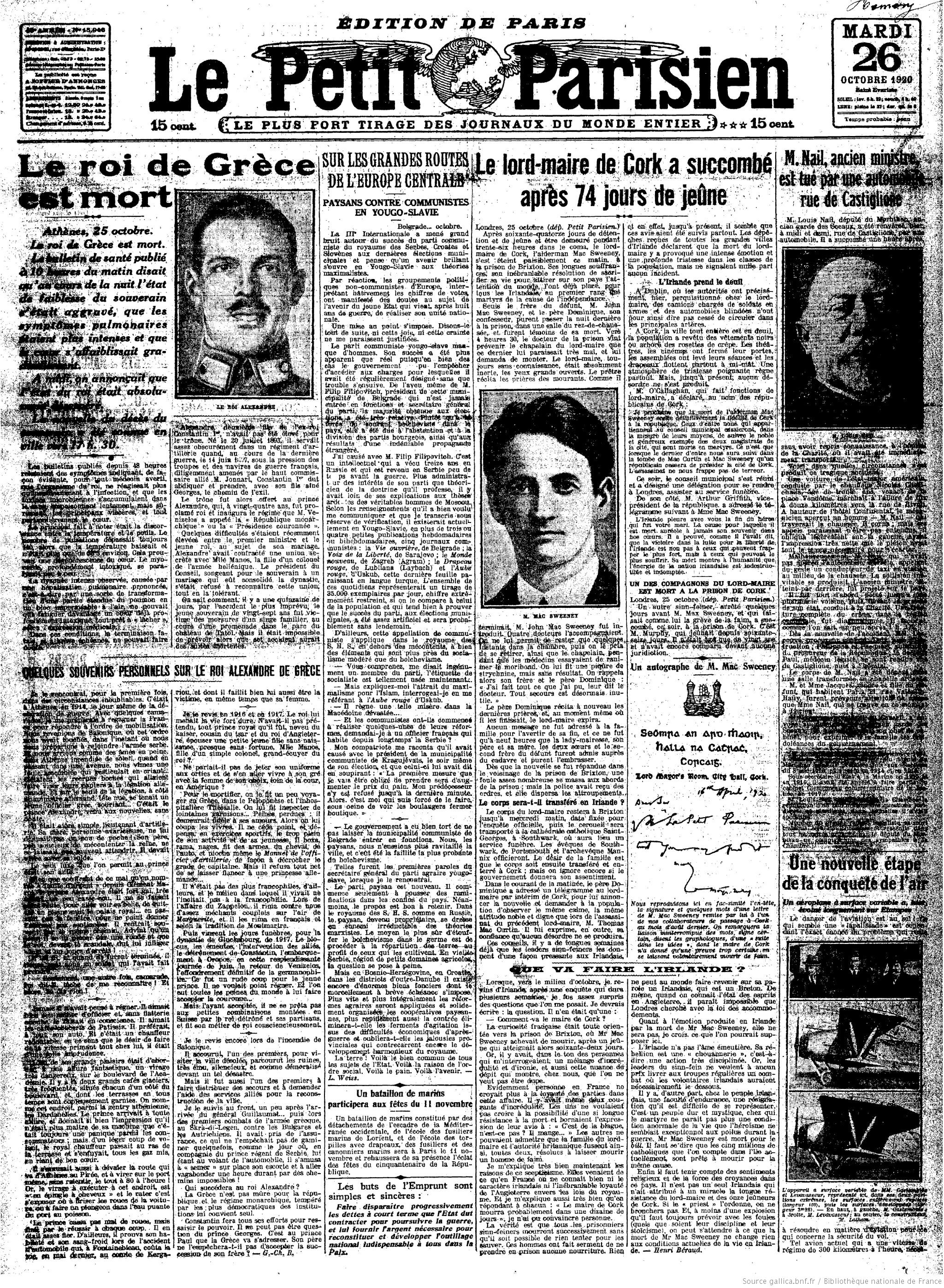

During the twentieth century French newspaper editors sent the grands reporters to Ireland at times of great importance in Irish history. This included times such as the 1916 Easter Rising, the Irish War of Independence, the Civil War and more recently the conflict known as ‘The Troubles’ in Northern Ireland. It is clear that the French newspaper reading public were interested in what was happening in Ireland, otherwise newspaper editors would not have sent reporters to Ireland. The death of the Lord Mayor of Cork, Terence Mac Swiney, after seventy four days on hunger strike in Brixton Prison marked a significant point in Ireland’s struggle for independence. As figure 1 above shows, reports of his death on the 25th of October 1920 were given as much prominence as the death of the King of Greece in the French newspaper Le Petit Parisien on the 26th of October.

Ireland in the 1920s through French eyes

Two young French reporters, who would go on to be very famous authors, reported from Ireland during the year 1920. Henri Béraud was writing for the left leaning newspaper Le Petit Parisien and Joseph Kessel was writing for La Liberté, a right leaning newspaper. These two young men travelled around the island of Ireland and met with many of the people who helped bring about change, such as the Sinn Féin leadership and some very shadowy figures in Dublin Castle. While in Ireland they reported on some of the events that brought about Ireland’s freedom, including the sack of Balbriggan and the killing of a policeman in Belfast, in retaliation for the killing of three Sinn Féiners the previous day.

Obviously well connected, both Kessel and Béraud met the commander of the British troops in Ireland, General Macready. He assured them that he could not discuss matters of politics with them and that his sole purpose in Ireland was to maintain order in the country. Kessel secretly met Countess Marckievitz in a Dublin house while she was evading capture by British forces, after arranging a clandestine meeting with the aid of a Sinn Féin contact. Kessel spoke French with the Countess and he left the meeting in awe of what he perceived as one of the most accomplished and courageous women he ever met. Kessel visited the cities of Belfast and Cork, and while in Cork he talked with a young Professor Alfred O’Rahilly in the grounds of University College Cork (UCC). O’Rahilly was later Registrar (1920-1943) and President (1943-1954) of UCC. Béraud also travelled from Dublin to Cork and Belfast and was struck by the abject difference between the north and the south. While trying to explain the difference between the two parts of the island, he said: the inhabitants of the north go about making their fortune while the southerners believe in miracles.

A young French reporter named Simone Téry travelled to Ireland in August 1921 to find out for her readers whether the truce in the Irish War of Independence was sustainable or not. She met with many of the political leaders of the day and their words were faithfully reprinted on the front page of her newspaper L’Œuvre. Téry travelled to County Clare with Michael Brennan, who was the IRA commander in the county, to see for herself how the truce was holding up. She met with leading unionist politicians in Belfast. Back in Dublin, she interviewed political figures such as Eamon De Valera, Michael Collins, Erskine Childers and Desmond FitzGerald. She admired the tenacious spirit of the Sinn Féin leaders and was particularly impressed by Desmond FitzGerald, who was Minister for Propaganda at the time. He spoke to her in fluent French and when she came away from her meeting with him in Dublin’s Mansion House, Téry said “l’Angleterre aura du mal à réduire ces hommes-là” (England will have great difficulty in fighting such worthy opponents).

Northern Ireland’s ‘Troubles’ as reported in the French press

The painful recent period of Irish history known as ‘The Troubles’ was followed intently by many foreign media organisations, particularly French newspapers. French newspaper readers were keenly interested to know how a war could be taking place in Europe, only a couple of hours from Paris by plane. Journalists such as Richard Deutsch (1945- ) who worked for the newspapers Le Monde and Le Figaro and Sorj Chalandon (1952- ) who wrote for Libération, travelled often to Belfast and reported on the growing instability in the region.

Keeping alive the links with the golden age of French journalism, Chalandon refers to himself as a grand reporter. He has reported from many war zones around the world, including Lebanon, Iraq and Afghanistan, but says that the conflict in Northern Ireland, more than any other, has had some kind of pull on him and caused him to return many times over the years to write about what was happening there. He has won many prestigious French literary awards for his novel Mon traître which is set in Northern Ireland and was based on his friendship with a high profile Sinn Féin member who was also a British army informant. The book has recently been translated into English under the title My Traitor and Chalandon was interviewed by Pat Kenny on RTÉ Radio 1 in May 2011, when it was launched in Ireland.

Conclusion

Whilst the relationship between France and Ireland has been documented in different forms and by many observers and commentators up to now, it has never been examined through the writings of French journalists before. Therefore, this research project, which uses original newspaper articles to get to the heart of why there are such close ties between the two countries, is both novel and exciting.

By writing about life in Ireland at key moments in the country’s birth and growth, French journalists have undoubtedly contributed in a positive way to creating an understanding of what life was like in Ireland. Their writings have given a voice to the voiceless and highlighted many injustices. We are interested in finding out what the journalists’ motivations were in relaying news from Ireland to the French newspaper reading public? Could it be simply a case of Ireland and France uniting in the face of a common enemy, i.e., Britain, or is that too simplistic a reading of the Franco-Irish relationship? It is said that journalism is the first draft of history and it is hoped that through this research, we will have a good idea of why there is such a close bond between our two countries.

I would like to thank my supervisor, Professor Grace Neville, the staff of the Department of French and my post graduate colleagues in University College Cork for all the help, encouragement and support they have given me. I would also wish to thank the Bibliothèque Nationale de France (BnF) for permission to reproduce the illustration featuring Le Petit Parisien.