Introduction

James Joyce’s Ulysses tells the story of a day in the life of a city. The city is Dublin and the main protagonists are Leopold Bloom, an advertising canvasser of Jewish race; his wife Molly, a singer who is having an affair with a concert promoter Blazes Boylan; and Stephen Dedelus, an aesthetic young teacher.

In eighteen episodes, Joyce uses Homer’s Odyssesy as a framework for his novel. Each episode is represented by a bodily organ which gives life to the city. Each episode also has an allotted hour of the day, and meals chart the progress of time. Bloom is introduced in Episode 4, ‘Calypso’, making breakfast in bed for Molly, and cooking a kidney for himself. Other episodes that I have mentioned in this paper are ‘Lestrygonians’, the land of the cannibals, which is almost entirely about food; ‘Cyclops’ which takes place in a pub; ‘Circe’ in a brothel; ‘Ithaca’ at the Bloom’s home where Leopold makes cocoa for Stephen and tries to entice him to come and live with them; and ‘Penelope’ which is narrated in Molly’s own voice, from the bed which has recently been vacated by Boylan.

This thesis looks at how food references are embedded in the text in a discourse that often has very little to do with food itself. By using a close critical reading of the primary text and an analysis that is based on archival, sociological and literary readings, I wish to prove that Joyce created a meta-text that not only used the visual, aural and olfactory representations of food to contextualise a city trapped between the famine and Irish Independence, but to make inferences such as Stephen’s rejection of solid food being related to issues of identity, and Bloom’s eclectic tastes in food as a sign of his otherness.

Methodology

Firstly I look at how Joyce uses this language of food to represent and authenticate the city. The city can be de-coded through the tangible evidence of newspaper cuttings, advertisements, diaries and his own letters, written at the time.

Secondly I look at how Joyce uses this language of food to engage with topics such as ritual, time, gender, politics, and otherness.

The result of this exploration is to show that Joyce’s language of food adds to and enhances our understanding of Ulysses. Building on the body of work that has already been carried out on the text, which primarily references alimentary and digestive issues, I hope to make the novel much more accessible. A psycho-nutritional reading can be used to look at the significance of food items that Joyce chooses, other than merely their requirement to fuel the body. Similarly the choices that Bloom and the other protagonists make point towards a cultural or political signification.

Joyce carefully chose every food item in Ulysses and each food that is selected is repeated throughout the text. Foods that first appear as an innocent ingredient for breakfast or on a market stall, become inflated with other or additional meanings. I call this Joyce’s food language or a meta-text, because by holding these individual items up for inspection, a whole story can be disentangled from each one. Whilst Joyce is initially depicting everyday life, the food becomes a fantastical means of escaping reality, particularly where it evolves, and returns in the hallucinatory brothel episode ‘Circe’.

Olives, Oysters and Oranges

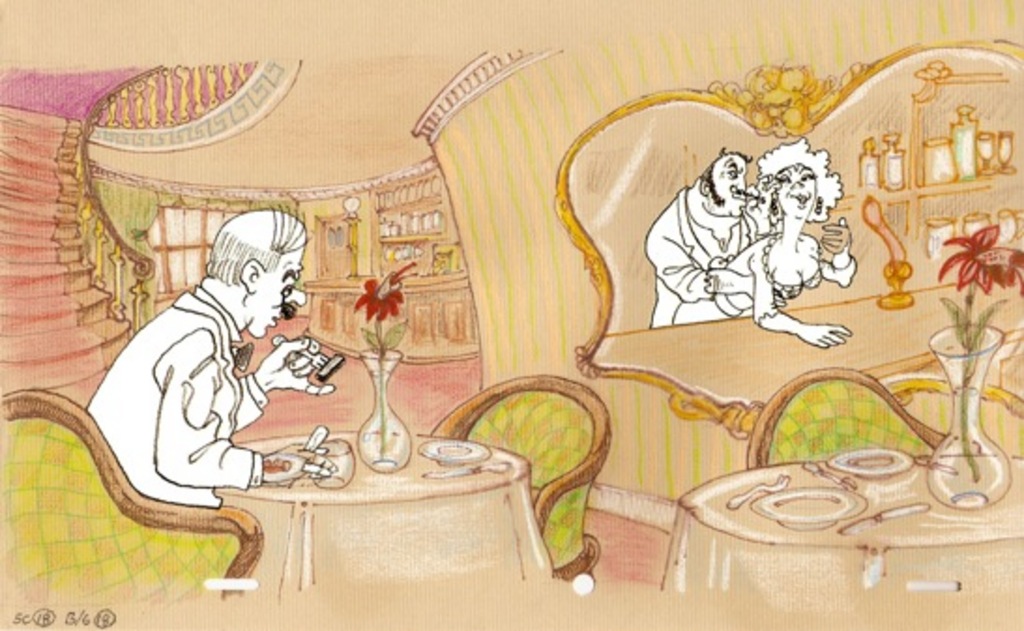

In the ‘Ithaca’ episode Bloom sees ‘Four black conglomerated olives wrapped in oleaginous paper’ languishing on the dresser in his kitchen. An unusual food, perhaps, to be found in the house of a lowly advertising canvasser, but Bloom seems to be familiar with many exotic foods, possibly because he was raised in the Jewish area of Dublin called Clanbrassil Street, where ethnic foods would have been more readily available. Indeed olives were for sale in Dublin, in Findlater’s price list for 1904 they are listed at 7d a jar. They were also for sale in Davy Byrne’s bar where Bloom contemplates eating them in a salad. This is a typical example of where historical fact intersects with literary fiction in the text. Bloom shows his familiarity with Mediterranean foods when he reads a handout from the model farm at Kinnereth, in Palestine, where the land is planted with olives, oranges, almonds and citrons. Ever practical, he considers how olives would be more economical to produce because they wouldn’t need much irrigation. In his mind’s eye, he can imagine attending to the pruning and ripening of the silver powdered trees and packing the olives in jars for sale. In this way he is able to escape the grey and paralysing atmosphere that he sometimes associates with Dublin. Once, he bought some olives for Molly to try but she spat them out. He thinks this is to do with the taste of them but later in the ‘Penelope’ episode she says that she could never bear to look at them. The drinkers in Barney Kiernan’s pub associate Molly with olives too because of her upbringing in Gibraltar where ‘loquat and almond scent the air’. ‘The garths of olives knew and bowed to Marion of the bountiful bosoms,’ one of them comments. Bloom, who continually ponders on, and enquires about the workings of, the world around him adds olives to the supper table in his imagined painting of ‘Jesus in the house of Mary and Martha’, which is in itself a meditation on the meaning of thought and the realm of ideas.

Similarly, Bloom is able to visualize oranges when he reads about them. He knows that they are packed in tissue paper in crates. Simultaneously he thinks about some friends of his in Dublin with the name Citron, whilst envisaging crates lined up on the quayside in Jaffa, handled by ‘navvies in soiled dungarees’. This is in ‘Calypso’, the first of the Bloom episodes, but by episode 17, ‘Ithaca’, he is still contemplating the reclamation of land for the cultivation of orange plantations, now adding that they should be fertilised by human excrement. These are the simple and everyday (albeit Mediterranean) connotations of growing oranges, but the word orange has other nuances. In ‘Nestor’ Mr Deasy, the headmaster, says to Stephen, ‘I remember the famine in ’46. Do you know that the Orange Lodges agitated for repeal of the Union twenty years before O’Connell did…?’ thereby referencing the famine and opening up issues of Unionism in a political thread which will run through the text and be exploited in a farcical rendering of a horse race in the nightmarish ‘Circe’, where the Orange Lodges goad Mr Deasy to ‘get down and push mister. Last lap’. The two fruits, olive and orange, are brought together in the facial features of Bella Cohen, the Madam of the brothel, who has an olive complexion with orange tainted nostrils. ‘Married I see,’ she accuses Bloom, ‘and the missus is the master. Petticoat government.’ Anticipating ‘Penelope’, in which Molly remembers how Bloom beseeched her to lift her orange petticoat so that he could rub his trouser leg against her.

Oysters were not an exotic food in 1904, 2/6 a dozen according to Molly, although Bloom thinks the price is kept up by throwing half the catch back in the sea. Molly accuses the maid, Mary Driscoll, of stealing oysters from their kitchen and gives her one week’s notice, ostensibly for the theft, but more likely because she suspects Bloom of having a dalliance with the maid. Then, as now, oysters carried overtones of sexuality and aphrodisia. Bloom says as much in ‘Lestrygonians’ when he gazes along the food shelves in Davy Byrne’s bar, but he also draws attention to how they are reared on sewage and he is inevitably reminded of Boylan. Molly’s thoughts also move from the maid and the oysters to Boylan, who, she thinks, must have been eating a lot of them judging by the size of his member and the way he sang during their lovemaking. Seconds later she confuses a story she has heard about a chastity belt with an oyster knife, which is surely not a coincidence. Like the other foods, oysters prefigure their interpretation in ‘Circe’, where Mary O’Driscoll appears as a witness accusing Bloom of inappropriate behaviour, and an apparition of Virag Lipoti (Bloom’s grandfather) is given the lines, ‘Red Bank Oysters will shortly be upon us. I’m the best o’cook. These succulent bivalves may help us …Though they stink yet they sing’. To which Bloom replies absently, ‘Ocularly woman’s bivalve case is worse. Always open sesame. The cloven sex.’ Oysters were, of course, forbidden by Jewish dietary law and Bloom never eats them himself.

Conclusion

These are just three examples of hundreds of foods that are referenced in Ulysses. Each food, deconstructed, points to a subtext that says much more about Bloom and about the city. A thread can be pulled, bringing together food items in their literal sense with more nuanced interpretations, until they are woven into a rich language. The authenticity of the city is established and through Bloom’s interaction with it we can see his vulnerability, his exclusion and his otherness. His choices around food can be seen sometimes as a desire to escape and sometimes a wish to conform. What we eat on what occasions makes for a ritual within the society we belong to, and defines who we are. Bloom knows that it is the kind of food we eat that makes us what we are. Bloom says that vegetarian food can make you ‘poetical’ but ‘you couldn’t squeeze a line of poetry’ out of ‘one of those policemen sweating Irish stew into their shirts.’

When Joyce was editing the proofs of his manuscript with many revisions and additions he was making a major shift from mere facts to symbolism. I believe the importance of my research is to unravel the food clues and interpret them as a language that will provide an innovative and contemporary reading, bringing Joyce’s great masterpiece to a wider audience, whilst academically enriching the field of study that has already been undertaken.

I would like to thank my Supervisor Dr Heather Laird for her wholehearted support, encouragement and specialist knowledge. Also my colleague Adrian Goodwin who has broadened my reading and understanding of literary theory.